Elizabeth Van Lew was a wealthy southerner from Richmond, Virginia who became a Union spy during the Civil War.

The following are some facts about Elizabeth Van Lew:

Elizabeth Van Lew’s Childhood:

Born on October 25th, 1818 into a slave-holding family, Van Lew learned to dislike slavery while attending a Quaker boarding school in Pennsylvania.

Following the death of her father in 1843, or 1851 (sources differ over the exact date), Van Lew’s mother inherited the bulk of the Van Lew estate.

With her father out of the picture, Elizabeth Van Lew managed to persuade her mother to free the family’s nine slaves and hire them back as paid servants, even though it was technically against the law to do so, according to an article in the New York Times:

“both Virginia state law and stipulations in her husband’s will impeded Mrs. Van Lew from legally manumitting any of her family slaves.”

Elizabeth Van Lew during the Civil War:

After the Civil War broke out with the attack on Fort Sumter on April 12th, 1861, the residents of Richmond took to the streets in a spontaneous celebratory parade which Van Lew watched mournfully, as she wrote in her diary:

“Such a sight! The multitude, the mob, the whooping, the tin-pan music, and the fierceness of a surging, swelling revolution. This I witnessed. I thought of France and as the procession passed, I fell upon my knees under the angry heavens, clasped my hands and prayed, ‘Father forgive them, for they know not what they do.'”

Van Lew, who went by the nickname “Lizzie,” began smuggling messages to the Union army, according to the book “More Than Petticoats: Remarkable Virginia Women”:

“The Van Lews owned a small farm on the James River, which Lizzie began using as a transfer point for information. She would use baskets of eggs to send messages to the Federal forces at Fort Monroe in Hampton. One egg in each group contained her message, torn into small pieces and inserted into the shell.”

After the Confederates set up various prisons in Richmond’s many tobacco warehouses, such as the Harwood tobacco factory and an old warehouse that became Libby Prison, Van Lew and her mother often visited the prisons, bringing food and medicine to the Union prisoners.

Elizabeth Van Lew

During their visits, they eavesdropped on the Confederate prison guards and gathered messages about the Confederate’s troop movements from prisoners, which they smuggled out of the prison inside books. Van Lew then sent this information to Union generals in coded messages.

During one of her visits, Van Lew also met Paul Joseph Revere, the grandson of American patriot Paul Revere, according to the book “More than Petticoats”:

“In January 1862, Paul Joseph Revere, the grandson of Midnight rider Paul Revere, was one of a group of prisoners moved from Harwood to the jail in Henrico. Miss Van Lew visited the jail, again bringing food and books. Revere’s group was exchanged for a group of Confederate prisoners, and Revere wrote to his family, telling them of Lizzie’s aid.”

Not only did Van Lew smuggle messages out of the prison, she also helped some of these prisoners escape by slipping them messages, hidden inside a secret compartment of a custard dish, with information and directions to local safe houses.

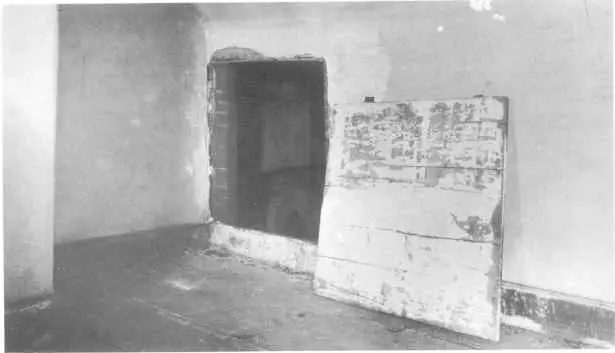

Secret room in the Van Lew mansion where Van Lew hid Unionists and escaped prisoners, circa 1890

To help break the prisoners out, Van Lew used her connections to get a Union sympathizer appointed to the prison staff.

During this time period, Van Lew allegedly acquired the nickname “Crazy Bet,” although many historians disagree on how or why she was given this nickname.

Some historians believe that Van Lew deliberately behaved as if she were mentally ill in public in the hopes that locals would ignore her and overlook her comings and goings, while other historians believe that locals nicknamed her “Crazy Bet” due to her status as a Southerner who supported the Union.

Elizabeth Van Lew

However she earned the nickname, the locals in Richmond greatly disapproved of her visits to the Union prisoners and the local paper, The Richmond Enquirer, often criticized her actions, without naming her specifically:

“Two ladies, a mother and a daughter, living on Church Hill, have lately attracted public notice by their assiduous attentions to the Yankee prisoners…. these two women have been expending their opulent means in aiding and giving comfort to the miscreants who have invaded our sacred soil.”

The Richmond Enquirer later published an article stating that if Van Lew didn’t stop her behavior she would be “exposed and dealt with as alien enemies of the country.”

Richmond residents quickly discovered her identity and made violent threats against Van Lew and her mother for their actions. It wasn’t long before they found themselves shunned by Richmond’s high society.

This did little to deter Van Lew and she continued to smuggle goods to prisoners, bribe guards to provide prisoners with extra food and medicine and even hid the prisoners she helped escape in her mansion.

General Butler’s Spy Network:

According to an article in Smithsonian magazine, after Union General Benjamin Butler heard stories about Van Lew from escaped Union prisoners in December of 1863, he recruited her to work as the head of his spy network and chief source of information about Richmond.

While working for Butler, Van Lew learned many tricks of the trade, such as how to write messages in code in a colorless liquid that turned black when combined with milk.

The information Van Lew gathered during this time period was later credited by Ulysses S. Grant as “the most valuable information received from Richmond during the war.”

Van Lew also managed to persuade Butler to raid Richmond in an attempt to free the Union soldiers held there, according to the book “More Than Petticoats”:

“Elizabeth began a correspondence with General Benjamin Butler, urging a raid on Richmond to free the many Union prisoners. Butler sent her letter to the secretary of war, who arranged for a force of 3,500 cavalrymen to march on the city, led by General Judson Kilpatrick and Colonel Ulric Dahlgreen. The group split, with Kilpatrick heading south, Dahlgreen southwest. When Dahlgreen reached the James River , it was impassable. Angry, he attacked farms and and the canal and hanged his scout. Meanwhile, Kilpatrick’s attack was stopped by the home guard, and the alarm was sounded. He retreated southeastward. When Dahlgreen’s troops followed, Dahlgreen rode out in front, confronted the Confederates near the Mattaponi River, and was shot. One hundred thirty-five of his soldiers and forty free blacks were captured. Dahlgreen’s artificial leg was taken as a souvenir, and he was buried in a shallow grave. Confederate President Jefferson Davis had Dahlgreen’s body brought to Richmond and secretly buried in Oakwood cemetery. A Unionist who witnessed the burial reported to Elizabeth Van Lew, who arranged for another burial. The exhumed corpse was placed in a wagon, driven past the Confederates to a farm north of Richmond, and reburied. When the Dahlgreen family requested the body from President Davis, the grave was found to be empty. After the war, Elizabeth Van Lew told the family where the body could be found.”

Butler himself praised Van Lew’s loyalty and contributions to the Union cause in a letter to Brigadier General John A. Rawlins on April 19, 1864:

“I enclose to you the examination of a messenger from Richmond. He comes to me from a reliable source, and I have no doubt of the reliability of the information he brings so far as the knowledge of the person who extends it. Miss Eliza mentioned, is a lady from Richmond of firm Union principles, with whom I have been in correspondence for months, on whose loyalty I would willingly stake my life. The information which she sends is what is known to the Union people of Richmond. Thinking it might be useful to the Commgd. General, I take the liberty of sending it to you.”

Van Lew soon set up a vast spy ring in the south. Some of her spies worked as clerks in the War and Navy Departments of the Confederacy, railroad officials, merchants and even as an (unsuccessful) candidate for Richmond mayor.

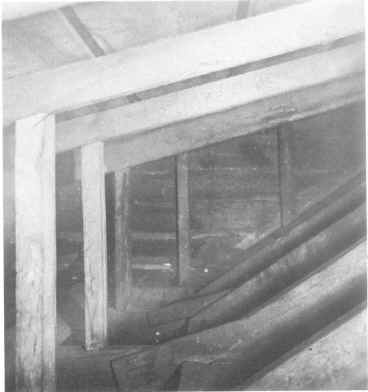

The secret passage in the Van Lew mansion where Van Lew hid Unionists and escaped prisoners during the Civil War, circa 1890

Many of her spies were her former slaves, such as Mary Elizabeth Bowser. Van Lew had arranged through a friend for Bowser to work as a servant in Jefferson Davis‘ Confederate White House in 1863.

Bowser, who had been educated at a Quaker school, had a photographic memory and stole glances at Davis’ important papers and documents on his desk.

She also eavesdropped on Davis and his colleagues as they discussed military plans over dinner. Bowser than transmitted the information to another spy, a baker named Thomas McNiven who made deliveries to the house.

In 1865, Davis eventually figured out there was a spy in his house and suspected Bowser. She was never caught but unsuccessful tried to burn the house down before she left her position.

Elizabeth Van Lew After the Civil War:

Eventually the long war ended and Van Lew was given many personal thanks from U.S. Generals and a little money as payment for her work, but her vast fortune was depleted and she was labeled a spy and ostracized from Richmond society.

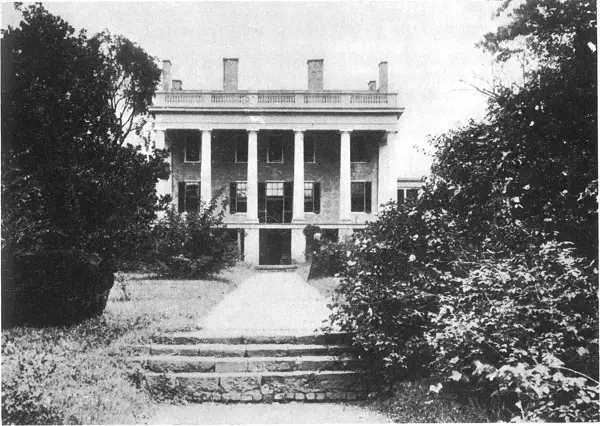

Van Lew Mansion, from the south, circa 1890 Elizabeth Van Lew stands at right center

After Ulysses S. Grant became president in 1869, he appointed Van Lew postmaster of Richmond. She held the job for eight years until Rutherford B. Hayes became president and she was replaced.

Penniless and with no one to turn to, Van Lew contacted the family of Colonel Paul Joseph Revere (grandson of Paul Revere), whom she had helped when he was imprisoned at the jail in Henrico.

The family set up a bank account for Van Lew with contributions from the families of Union prisoners Van Lew helped in Richmond. Van Lew lived off these contributions for the remainder of her life.

After Van Lew became ill in the winter of 1900, she told her nieces about her secret diary she kept hidden in her backyard for 40 years.

Van Lew Mansion, south portico, circa 1890. Elizabeth Van Lew is seated at left

Her nieces dug the diary up and brought it to her, but Van Lew noticed much of the diary was missing. The missing sections were never recovered and Van Lew died in September of 1900.

According to the book “Women in the Civil War,” Revere’s family paid for Van Lew’s funeral and bought her a special headstone:

“After her death, relatives of Colonel Revere (whom she had helped escape), bought a headstone for her grave. The headstone was made of Massachusetts granite with a bronze plaque that read: ‘She risked everything that is dear to man – friends, fortune, comfort, health, life itself. All for the one absorbing desire of her heart – that slavery might be abolished and the Union preserved.’ The stone has this marking: ‘This boulder from Capital Hill in Boston is a tribute from her Massachusetts friends.'”

Sources:

“Women in the Civil War: Extraordinary Stories of Soldiers, Spies and Nurses”; Larry G. Eggleston; 2003

“More Than Petticoats: Remarkable Virginia Women”; Emilee Hines; 2003

“The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant: January 1 – May 31st”; Ulysses Simpson Grant”; 1982

New York Times; A Black Spy in the Confederate White House; Lois Levenn; June 21 2012: http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/06/21/a-black-spy-in-the-confederate-white-house/

New York Times; Women at War; Elizabeth R. Varon; February 1 2011: http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/02/01/women-at-war/

National Security Agency; Women in Cryptological History; Elizabeth Van Lew: http://www.nsa.gov/about/cryptologic_heritage/women/honorees/van-lew.shtml

National Park Service: Elizabeth Van Lew: http://www.nps.gov/resources/person.htm?id=116

Central Intelligence Agency: Civil War; Elizabeth Van Lew: https://www.cia.gov/kids-page/6-12th-grade/operation-history/civil-war.html#liz

Smithsonian Magazine; Elizabeth Van Lew: An Unlikely Union Spy; Cate Lineberry; May 2011: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/Elizabeth-Van-Lew-An-Unlikely-Union-Spy.html

I have enjoyed your posts of late, especially the ladie spies. That is an area I do not know much about so your posts are helping me learn more about them. I do hope you are considering one about Pauline Cushman, since I had never heard of her! And as always, thanks for the source list.

Thanks Steve! Yes, I’m definitely going to write a post about Pauline Cushman and the other female spies and soldiers. I find them fascinating and I feel they don’t get the recognition they deserve.

why did Elizabeth Van Lew become a spy

she wanted to become a spy because she wanted to end slavery

What are her nieces names

Sorry, I don’t know.

I am doing a essay on Elizabeth Van Lew. Thank you, this was very helpful.