African-Americans who served as soldiers in the Civil War didn’t receive the same treatment as white soldiers.

When African-American soldiers were finally allowed to enlist in the Union army in the summer of 1862, they quickly discovered they earned much less than white soldiers.

Black soldiers earned $10 a month while white soldiers earned $13. On top of the that, black soldiers were also charged $3 a month for clothing fees, further reducing their pay to $7.

To protest their low pay, which the military argued was justified by the Militia Act of 1862 – a law that was intended to let former slaves become laborers for Union army forces occupying the south but instead created regiments of black soldiers, these black soldiers refused to accept any money until their pay was raised.

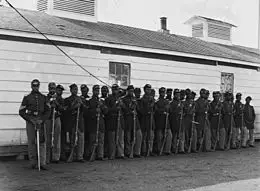

Company E, 4th United States Colored Infantry at Fort Lincoln on November 17, 1865

Many soldiers, including Corporal James Henry Gooding, even wrote letters to Lincoln asking that he pay black soldiers the same as white:

“Now the main question is. Are we Soldiers, or are we LABOURERS. We are fully armed, and equipped, have done all the various Duties, pertaining to a Soldiers life, have conducted ourselves, to the complete satisfaction of General Officers, who, were if any, prejudiced against us, but who now accord us al the encouragement, and honour due us. . . .have dyed the ground with blood, in defense of the Union, and Democracy. . . . We have done a Soldiers Duty. Why cant we have a Soldiers pay?”

In November of 1863, Sgt. William Walker of South Carolina convinced a group of his fellow soldiers to go on strike until they received equal pay.

When army officials threatened to charge the soldiers with mutiny, most of them went back to work. Sgt. Walker refused and in February he was tried, convicted and executed by a firing squad.

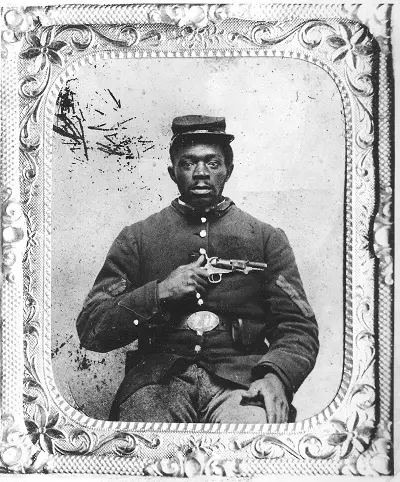

Nimrod Burke of the 23rd United States Colored Infantry Regiment

Soon abolitionist groups, newspapers and politicians took up the cause and began lobbying for an increase in pay for the black soldiers.

Abolitionist Harriet Tubman later stated in an interview that when she heard of the pay difference for black soldiers it turned her against Abraham Lincoln and she refused to meet him out of protest.

Finally, in June of 1864, Congress passed a law enforcing equal pay. The problem was the pay was retroactive only until the previous January 1st for most soldiers and from the time of enlistment for men who were already free before the Civil War began on April 19, 1861.

As many black soldiers were runaway slaves or were freed only after the Union army raided their town, this did not apply to many of them.

Several troop leaders found a way around the restriction by allowing their soldiers to take the Quaker Oath, which declared that by God’s law, instead of man’s law, they “owed no man unrequited labor on or before the 19th day of April, 1861.”

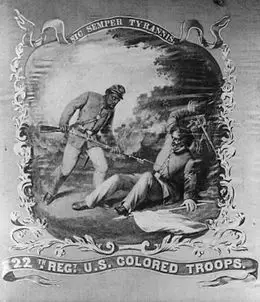

Banner for the 22nd U.S. Colored Troops

The protests about back pay continued until March of 1865 when Congress finally awarded all black soldiers back pay retroactive to their actual enlistment dates.

To find out more information about the roles African Americans played in the Civil War, check out the following article: African-Americans in the Civil War.

Sources:

National Geographic; African-Americans in the Civil War; Shelley Sperry

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0504/feature5/online_extra.html

National Park Service; Fort Smith’s United States Colored Troops

http://www.nps.gov/fosm/historyculture/fort-smiths-united-states-colored-troops.htm

“Black Heritage Sites: The South”; Nancy C. Curtis; 1996

“The African American Soldier”; Michael L. Lanning; 2004

“A Grand Army of Black Men: Letters from African-American Soldiers in the Civil War”; Edwin S. Redkey; 1992

This is why critical race theory needs to be taught