One of the many roles of women in the Civil War was that of a soldier. Due to the fact that women were not allowed to serve in the military at the time, these women disguised themselves as men, cut off their hair and adopted male aliases in order to join the military.

How Many Women Fought in the Civil War?

According to the American Battlefield Trust, between 400 to 750 women fought as soldiers in the Civil War. The authors of the book They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War give a different number though, stating that they found a total of 250 documented cases of women serving as soldiers in the war but they suspected there were many more than that.

In May of 1864, a year before the war finally ended, the Nashville Dispatch reported that, according to official records at Washington, over 150 female soldiers had been discovered since the war began:

“The official records at Washington state that upward of 150 female recruits have been discovered since the commencement of the war. It is supposed that nearly all of these were in collusion with men who were examined and accepted, after which the fair ones managed to substitute themselves and be mustered into the service. Over seventy of these martial ladies, when their sex was discovered, were acting as officers servants. In one regiment there were seventeen of them in this capacity.”

It is hard to pinpoint the exact number of women who fought in the war due to the secrecy of what they were doing. The only reason we know of these women at all is because their real identities were discovered and documented at some point.

Some of these women were discovered while in service either because they were wounded, captured or died and, as a result, they were physically examined by doctors. The discovery of their true identity usually resulted in some kind of paperwork, either through discharge papers, letters between military officials, death certificates and etc, which would have left a paper trail of documented evidence.

Other women confessed to their actions, either through letters to friends and families, or by writing memoirs about their experiences and even by applying for Civil War pensions which required them to provide proof of service and reveal their aliases.

Other times, their military service was made public for the first time when they passed away, years after the war, and their military service was revealed in their obituary. For the women who were never discovered, and historians suspect there were many, their stories remain lost forever.

Women soldiers fought in some of the biggest and most famous Civil War battles. It was often when these women soldiers were wounded that their real identities were discovered. Wounded women soldiers were discovered at the Battle of Shiloh, Battle of Richmond, Battle of Perryville, Battle of Murfreesboro, Battle of Antietam, Battle of Fredericksburg, Battle of Gettysburg, Battle of Green River, Battle of Lookout Mountain, Battle of Peachtree Creek, Battle of Allatoona, the Battle of the Wilderness and etc.

In addition, dead women soldiers were also discovered at the First Battle of Manassas, Second Battle of Mannassas, Battle of Shiloh, Battle of Gettysburg, Battle of Resaca, Battle of Dallas, Battle of the Crater, Battle of Petersburg and the Battle of Appomattox.

The actions of these women soldiers have been forgotten over time but the public was well aware of the women soldiers at the time of the Civil War because their stories were routinely reported in newspapers across the country.

Why Did Women Fight in the Civil War?

Since there isn’t a lot of documentation on why most of these women joined the army, it is assumed that they joined for the same reasons men did. These reasons include money, patriotism, adventure and a chance to travel.

These women soldiers tended to be young, unmarried, childless and poor which meant they didn’t have a lot of obligations at home to keep them from going to war.

A few women soldiers actually published memoirs, wrote letters during their time in service or gave interviews with reporters and explained their personal reasons why they decided to fight in the war.

Frances Clayton, photographed by Samuel Masbury, circa 1865

Loretta Janeta Velazquez, a southern woman who joined the Confederate army and later wrote a memoir about her experience, titled The Woman In Battle: A Narrative of the Exploits, Adventures and Travels of Madame Loreta Janeta Velazquez, explained that she had always had fantasies about going off to war like her hero, Joan of Arc, and the Civil War was her opportunity to act on those fantasies. Although she was married and had children, when her children died of an illness and her husband left for war, she decided it was finally her moment:

“About the time [1860] my two remaining children died of fever, and my grief at their loss probably had a great influence in reviving my old notions about military glory, and of exciting anew my desires to to win fame on the battle-field. I was dreadfully afraid that there would be no war, and my spirits rose and sank as the prospects of a conflict brightened or faded…As for me, I was perfectly wild on the subject of war; and although I did not tell my husband so, I was resolved to forsake him if he raised his sword against the South. I felt that now the great opportunity of my life had arrived, and my mind was busy night and day in planning schemes for making my name famous above that of any of the great heroines of history, not even excepting my favorite, Joan of Arc.”

Romantic notions about following in the footsteps of Joan of Arc were quite common among these young women. In 1864, the Brooklyn Daily Times published an article about a young Brooklyn woman named Emily who fought and died at the Battle of Lookout Mountain.

According to the article, Emily had been suffering from what the newspaper called a “sad case of monomania” and believing that “she was a second and modern Joan of Arc, called by Providence to lead our armies to certain victory in this contest” she escaped her physicians in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where she was being treated, and ran away to join the drum corps of a Michigan regiment in the Army of Cumberland. While dying of a mortal wound received in battle she dictated a letter to her parents that read:

“Forgive your dying daughter. I have but a few moments to live. I expected to deliver my country, but the fates would not have it so. I am content to die. Pray, Pa, forgive me. Tell ma to kiss my daguerreotype. Emily.”

Another female soldier, Sarah Rosetta Wakeman, wrote in a letter to her parents that her reason for joining was out of a desire to help her family and to find adventure:

“I can tell you what made me leave home. It was because I had got tired of stay[ing] in the neighborhood. I knew that I could help you more to leave home than to stay there with you…I [am] enjoying myself better this summer than I ever did before in this world. I have good clothing and enough to eat and nothing to do, only to handle my gun and that I can do as well as the rest of them.”

Yet another female soldier, Annie Lillybridge, was identified as a woman and, during an interview with the Chicago Post in 1863, explained her reason for joining was because she had fallen in love with a lieutenant in one of the Michigan regiments and didn’t want to be without him:

“The thought of parting from the gay lieutenant nearly drove her mad, and she resolved to share his dangers and be near him. No sooner had she resolved upon this course than she proceeded to act. Purchasing male attire she visited Ionia, enlisted in Captain Kavanah’s Company, 21st Regiment. While in camp, she managed to keep her secret from all – not even the object of her attachment, who met her every day, was aware of her presence so near him.”

Another women, Frances Hook, told her family that she had joined the army, serving under the alias Frank B. Miller, and when she was scolded by her brother, who was also a soldier, she explained that she joined for the same patriotic reasons he did:

“My Dear Brother, I wish to say that in reply to your recent letter that I volunteered in the army because I wished to have a part in the defense of my country’s flag. I think I love my country as well as you do, and by sufficient drilling I think I may learn to shoot just as straight as you can and if my health continues good I may be of equal service as that of yourself.”

As to how this many women suddenly came up with the idea to disguise themselves as men and go off to war, the authors of the book They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War, explain that they were most likely inspired by the many cross-dressing heroines that were popular in Victorian culture at the time:

“There was no public recruitment of women into the army, yet significant numbers of them decided to enlist anyway, each making an independent decision to dress as a man and march off to war. How did so many women reach the same conclusion? The answer is that cross-dressing female heroines, both fictional and real, were a standard commodity in popular culture. In fact, military and sailor women were celebrated in popular novels, ballads, and poetry from the seventeenth century through the Victorian age. Inspired by and created for an audience of literate but lower and working-class people, the woman warrior was a virtuous and heroic ideal. Dianne Dugaw labels this literary phenomenon ‘the Female Warrior Motif,’ explaining that these fictional and semifictional women and their narratives conformed ‘to an ideal type – a conventionalized heroine who, pulled from her beloved by ‘war’s alarms’ or a cruel father, goes off disguised as a man to sea or to war…[The] transvestite heroine a model of beauty and pluck, is deserving in romance, able in war, and rewarded in both.’ The women soldiers of the Civil War may very well have been inspired by the fictional Sarah Brewer, the female marine of the War of 1812 (although this heroine dressed as a man to escape the life of a prostitute), or any number of European examples, both true and legendary, whose stories were widely available prior to the war.”

Velazquez stated in her memoir that she didn’t feel the act of dressing up as man was strange at all and felt she brought honor to the Confederate uniform:

“I can only say, however, that in my opinion there was nothing essentially improper in my putting on the uniform of a Confederate officer for the purpose of taking an active part in the war; and, as when on the field of battle, in camp, and during long and toilsome marches, I endeavored, not without success, to display a courage and fortitude not inferior to the most courageous of the men around me, and as I never did aught to disgrace the uniform I wore, but on the contrary, won the hearty commendation of my comrades, I feel that I have nothing to be ashamed of.”

List of Documented Women Civil War Soldiers:

The names of the the following women soldiers come from multiple sources such as as old newspaper articles as well as the book They Fought Like Demons which uncovered them in various documents such as military records, published diaries, letters and memoirs.

In some cases, only the women’s male alias is known and in other cases only the women’s first name is known. Unfortunately, in many cases, when women soldiers were discovered the press reports or military documents about them intentionally excluded their names to protect their identities.

The following is a list of documented women soldiers and their names and/or aliases:

• Alias Private Arnold (real name unknown), served in a Kentucky Regiment, Confederate army, surrendered herself to the mayor of Richmond in 1862 fearing she had been detected, story reported in the press at the time of her surrender

• Sarah Malinda Pritchard Blalock, alias Sam Blalock, 26th North Carolina Infantry, Confederate army

• Mary Burns, 7th Michigan Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, Union army

• Sarah Bradbury, alias Frank Morton, 7th Illinois Cavalry, 2nd Kentucky Cavalry, her real identity was discovered after she got drunk with another female soldier, Frances Hook, and they both fell into a river for which they received medical attention. They were both sent home but Hook joined another regiment and continued fighting.

• Mollie Bean, 47th North Carolina, Confederate army, her real identity was discovered after she was captured in Richmond in 1865, she was imprisoned at Castle Thunder

• Mary and Mollie Bell, aliases Tom Baker and Bob Morgan, two cousins who served in the 36th Virginia infantry, Confederate army, arrested after confessing their real identities to their commander and imprisoned at Castle Thunder in 1864

• Mrs. Blaylow, Confederate army, joined to follow her husband and eventually revealed her identity herself in order to accompany her husband home after he was discharged in 1862

• Frances Clayton, alias Jack Williams, 4th Missouri artillery, her real identity was discovered after she was wounded in the Battle of Shiloh, she was discharged in 1863

• Lizzie Compton, 11th Kentucky Cavalry,125th Michigan Cavalry, 21st Minnesota Infantry, 8th, 17th and 28th Michigan infantry, 79th New York Infantry, 3rd New York Cavalry, holds the record for the most amount of reenlistments, her real identity was discovered many times and she continued to reenlist in other regiments after being discharged

• Amy Clark, alias Richard Anderson, 11th Tennessee Infantry, Confederate army, captured at the Battle of Richmond

• Sarah Collins, Wisconsin native, her real identity was discovered, due to the way she put on her shoes, before her regiment left for battle

• Nancy Corbin, Tennessee native, joined the army to find her boyfriend

• Mrs. Curtis, 2nd New York Regiment, Union army, captured at the Battle of Fall’s Church, imprisoned in Richmond

• Mary W. Dennis,1st lieutenant of the Stillwater Company, Minnesota regiment

• Alias Frank Deming (real name unknown), 17th Ohio Infantry, discharged in 1862 when her real identity was discovered

• Loretta De Camp, joined a regiment under the command of Colonel Dreux, Confederate army, her identity was discovered and she was sent home, rejoined and served as 1st lieutenant in Captain Phillip’s Company in the Independent Tennessee Cavalry, taken prisoner and exchanged, rejoined and served as 1st lieutenant in the Adjunant General’s Department, she ceased being a soldier and instead served as a spy

• Catherine E. Davidson, Ohio native, wounded at the Battle of Antietam

• Emily (last name unknown), joined a drum corp in a Michigan regiment, mortally wounded at the Battle of Lookout Mountain, confessed her real identity while dying, Brooklyn Daily Times reported her story in 1864 shortly after her death but excluded her last name to protect her identity

• Mary Fitzallen, alias Harry Fitzallen, 23rd Kentucky Regiment, Union army, arrested and fined in 1862 for impersonating a man

• Mary Galloway, Maryland native, Army of the Potomac, wounded at the Battle of Antietam and her real identity was discovered by Clara Barton, she made a full recovery and returned home and Barton helped reunite Galloway with her boyfriend by locating him in a Washington hospital

• Marian Green, 1st Michigan Engineers and Mechanics regiment, her parents discovered what she was doing and arranged to have her return home

• Mary Jane Green, Confederate army, imprisoned seven times after her real identity was revealed and holds the record for the most amount of Civil War incarcerations for a woman, she was repeatedly released when she promised to leave the army but continued to serve

• Nellie Graves, 24th New Jersey Infantry Regiment, enlisted alongside her friend Fannie Wilson, the identities of both women were discovered when they took ill and they were discharged, it is rumored that Graves reenlisted

• Lucy Matilda Thompson Gauss, alias Private Bill Thompson, 18th North Carolina Infantry, Confederate Army, took a permanent furlough when her husband was killed at the Seven Days Battle

• Jennie D. Hart, Jenkin’s Cavalry, Confederate army, captured in Virginia in 1863 and imprisoned at Fort McHenry

• Frances Hook, alias Frank Miller, 65th Home Guards in Illinois and then the 90th Illinois Regiment, captured and her real identity was discovered, she was exchanged in 1864

• Louisa Hoffman, alias John Hoffman, 1st Virginia Cavalry, 1st Tennessee Artillery, her real identity was discovered and she was arrested and sent home to New York City in 1864

• Satronia Smith Hunt, served in an Iowa Regiment with her husband, he died in battle but she survived the war unharmed

• Lizzie Hodge, her real identity was discovered and she was arrested in Bowling Green in 1864 and released to the care of her sister

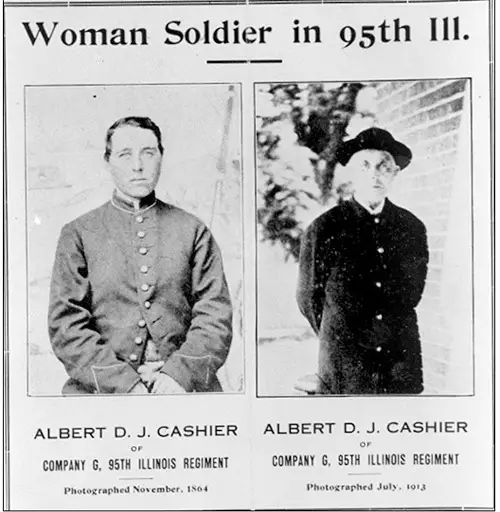

• Jennie Hodgers, alias Albert Cashier, 95th Illinois Infantry, served for three years until her unit was mustered out in August of 1865, was never detected and continued to live as man, in 1913 she was sent to a mental hospital for dementia and real identity was discovered, the press caught wind of her story and reported on it

• Margaret Henry, Confederate army, captured with another female soldier Mary Wright while burning bridges around Nashville

• Mrs. Irvin, alias Charley Green, quit the army and resumed her real identity to become a nurse

• Nellie K., 102 New York Infantry, enlisted with her brother and was discharged once her real identity was discovered

• Mary Jane Johnson, 16th Maine Regiment, Union army

• Jenny Lockwood, 2nd Michigan Infantry, she confessed her identity after the war when she appeared at local police station and told them she was a veteran and that she was “sick and without a home”, the police brought her to a local hospital

• Maria Lewis, an African-American woman who served in the Ace New York Volunteer Cavalry, it is assumed she was light-skinned enough to pass as a white man or Native-American

• Alfred J. Luther, sergeant in the 1st Kansas Infantry, died of smallpox in 1863, her identity was revealed after her death in a letter written by Lieutenant Frederick Haywood to his sister in 1863

• Annie Lillybridge, 21st Michigan infantry, Union army

• Martha Lindley, alias Private Jim Smith, mustered out of her regiment in August of 1864

• Frank Martin, her real name remains unknown, 2nd Tennessee Cavalry, 8th and 25th Michigan Infantry, she was discovered twice but refused to identify herself, she was mustered out of her regiment the first time but was allowed to remain in her regiment the second time and worked as a field nurse

• Mrs. McDonald, Col. Boone’s Regiment in KY, her real identity was discovered twice and she was discharged both times

• Marian Mckenzie, alias Henry Fitzallen, 23rd Kentucky Volunteer Infantry, 8th and 92nd Ohio Infantry, was discovered three times and discharged but continued to reeinlist and was eventually mustered out of the military for good in 1865

• Margaret Catherine Murphy, alias private Joseph Davidson, 98th Ohio Infantry, after her real identity was discovered she was suspected of being a Confederate spy and was imprisoned and then exiled to the south where she was captured by the Confederates and sent back to the Union and imprisoned again for the remainder of the war

• Elizabeth Niles, some records say she served in the 4th New Jersey Infantry while other records say she served in the 14th Vermont Infantry

• Mary Owens, alias John Evans, Pennsylvania native, Union army, her real identity was discovered when she was wounded in the arm, served in the army for 18 months

• Elizabeth Price, Ohio regiment, arrested in Louisville in 1864

• Melverina Elverina Peppercorn, Confederate army, enlisted alongside her twin brother, Alexander, in 1862, Alexander was wounded and served as his nurse in the hospital, the twins tried to reenlist after he recovered but by then the war was nearly over

• Jane A. Perkins, Confederate army, captured and taken prisoner

• Rebecca Peterman, 7th Wisconsin Infantry, served for two years until she was wounded in battle

• Mary Ann Pitman, alias Second Lieutenant Rawley, Confederate army

• Alias Charlie (real name unknown), fought at the First Battle of Bull Run

• Margaret (last name unknown), fought at the Second Battle of Bull Run

• Ida Remington, 11th New York Militia, her real identity was discovered when she was arrested for drunkenness in Harrisburg

• Mary Scaberry, alias Charles Freeman, 52 Ohio Infantry, enlisted in the summer of 1862, her real identity was discovered in November of that year when she contracted a fever, she was discharged from service

• Mary Siezgle, served alongside her husband in the Union army in a New York Regiment

• Diana Smith, Moccasin Rangers led by Captain Kesler, Confederate army

• Alias Charles H. Williams (real name unknown), Iowa native, enlisted because she was in love with a lieutenant

• Miss Weisener, Alabama native, joined a regiment in the Confederate Army alongside her husband

• Jane Short, alias Charlie Davis, 21st Missouri Regiment, 6th Illinois Cavalry,

• Loreta Janeta Velazquez, Confederate army, her real identity was discovered many times and she was fined and discharged repeatedly but continued to reenlist until, after being wounded in battle and her secret was discovered again she quit the army for good

• Laura J. Williams, alias Henry Benford, 5th Texas Volunteers, became ill and quit the army to become a spy

• Sarah Williams, alias John Williams, 2nd Kentucky Cavalry, her real identity was discovered after three years in service and she was arrested and sent to the Post prison in 1864.

• Anne Williams, alias Mrs. Arnold and Mrs. Williams, 7th and 11th Louisiana Regiment, arrested for robbery and sentenced to six months in prison in 1862

• Fannie Wilson, 24th New Jersey Infantry Regiment, enlisted alongside her friend Nellie Graves, arrested for impersonating a Union soldier after her real identity was discovered in 1864 and was discharged, she quickly reenlisted

• Mary Ellen Wise, Indiana regiment, wounded at the Battle of Lookout Mountain after which her identity was discovered, took a job as a nurse in a hospital in Louisville, Washington Daily Morning Chronicle reported on her story in 1874 in an article titled “Brave Soldier Girl”

• Sarah Rosetta Wakeman, alias Lyons Wakeman, 153rd Regiment of the New York State Volunteers, died of illness in 1864, her identity was revealed after her parents published her letters describing her military service

• Lilly White, 23rd Alabama Regiment, died from a wound received in a train accident in 1862

• Mary Wright, captured with Margaret Henry while burning bridges around Nashville

Primary Sources of Female Soldiers in the Civil War:

• The Woman In Battle: A Narrative of the Exploits, Adventures and Travels of Madame Loreta Janeta Velazquez by Loreta Janeta Velazquez

• An Uncommon Soldier: The Civil War Letters of Sarah Rosetta Wakeman by Sarah Rosetta Wakeman, Lauren Cook Burgess, Lauren M. Cook

• University of Texas at Tyler: Women Soldiers, Spies, and Vivandieres: Articles from Civil War Newspapers: http://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=cw_newstopics

In addition to serving as soldiers, women also worked as spies, war relief workers and nurses during the Civil War.

Sources:

The Civil War Treasury by Albert A. Nofi

Civil War Trust: Jennie Hodgers: civilwar.org/education/history/biographies/jennie-hodgers.html

http://history.ky.gov/landmark/tell-her-what-a-good-rebel-soldier-i-have-been-mary-ann-clark-disguised-during-the-civil-war/

Women in the Civil War by Mary Elizabeth Massey

University of Texas at Tyler: Women Soldiers, Spies, and Vivandieres: Articles from Civil War Newspapers: scholarworks.uttyler.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=cw_newstopics

The Bugle Blast, Or, Spirit of the Conflict by J. Challen & Son

The Woman in Battle: A Narrative of the Exploits, Adventures, and Travels of Madame Loreta Janeta Velazquez by Lorate Janeta Velazquez

An Uncommon Soldier: The Civil War Letters of Sarah Rosetta Wakeman by Sarah Rosetta Wakeman, Lauren Cook Burgess, Lauren M. Cook

Smithsonian Associates: Why Did Women Fight in the Civil War?: civilwarstudies.org/articles/Vol_1/women-in-the-civil-war.shtm

Washington Post: Women Soldiers Fought Bled and Died in the Civil War, Then Were Forgotten: washingtonpost.com/local/women-soldiers-fought-bled-and-died-in-the-civil-war-then-were-forgotten/2013/04/26/fa722dba-a1a2-11e2-82bc-511538ae90a4_story.html

Civil War Trust: Female Soldiers in the Civil War: civilwar.org/education/history/untold-stories/female-soldiers-in-the-civil.html

The best estimate of female combatants in the Civil War has been provided in John A. Braden, “Mothers of Invention: Phony Reports of Female Civil War Combatants.” in the January/February, 2015 Camp Chase Gazette (Vol. XLII, NO. 1). Extrapolating from reports of captured female combatants, he estimates the total at 131. He also demonstrates that higher estimates are based on speculation and/or unreliable accounts.

1st Sergeant Mary Jane Wright served with Co. F, 4th Kentucky Cavalry. She enlisted or was recruited while Col. Henry L. Giltner’s 4th Kentucky Cavalry kept its headquarters in Wytheville, Virginia, during the spring of 1864. In December 1864 the 4th Kentucky Cavalry was camped at Wytheville when word arrived that Union General Stoneman, commanding a division of cavalry, was advancing from Tennessee with their objective being the salt mines at Saltville, Virginia. In an effort to stop them, the 4th Kentucky along with the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry met Union General Stoneman’s forces at Kingsport, Tennessee. The resulting battle was a defeat for the Confederate forces and resulted in the capture of scores of the Confederates on December 21. Among those captured was Company F’s 24-year old 1st Sergeant Mary Jane Wright. Along with her comrades, she was taken to Knoxville, transferred to Louisville on April 7, 1865, and finally transferred to Camp Chase, Ohio, Union prison.

She was in prison for almost five months. Upon taking the oath to the United States, she was released on May 11, 1865, and returned to Wythe County, Virginia.

Note that her service record verifies the above. Please include her in your accounts. You mention a Mary Wright captured near Knoxville. She is probably the same person.

Where could I locate published memoirs of woman who fought in the American Civil War?

On page 132 of Winston Groom’s “Shrouds of Glory” he says that in 1864 at the battle of Duck River, James Wilson (federal cavalry) took command of Army of Tenn around Nashville he spotted “a well mounted and well clad woman, riding with the field and staff…” as when asked, was told she was “Mrs. Colonel Smith commanding the Michigan 8th cavalry”. His text says that Wilson immediately relived her from further duties.

Do you know who he is talking about?