To get a better understanding of how the Civil War played out as it did, it is helpful to evaluate the strategies of both the North and the South in the Civil War.

The battles and events that took place were not random encounters or skirmishes but were instead, well-planned and thought-out strategies to secure supplies, keep lines of military communication open, prevent wide scale casualties and to gain and control more ground.

Both sides had their own ideas on how to accomplish this and the strategies they used have been widely scrutinized, studied, evaluated and recreated ever since.

In fact, numerous Civil War strategy games are based on these very strategies and some types of battle reenactments, such as tactical battles or tactical events, use these strategies to try to defeat their opponents in recreations of the battles.

The following is an overview of the strategies used in the Civil War:

Union Strategy:

At a cabinet meeting on June 29, 1861, Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, general-in-chief of the U.S. army and a veteran of the Mexican war, proposed a military strategy to defeat the Confederacy.

Although the Union had a large army on its side, Scott doubted the scores of newly recruited soldiers would be ready for battle in time and instead proposed that they isolate the South from the rest of the southern states.

The idea was that it would put an economic stranglehold on the Confederacy, isolate it from all sources of supply and allow for growth of anti-secessionist sentiments which would eventually cause the South to surrender without the use of violence and would therefore save more lives.

Scott further proposed that if the strategy didn’t work, the Union could raise an army of 300,000 soldiers that could invade the South and win the war within two to three years.

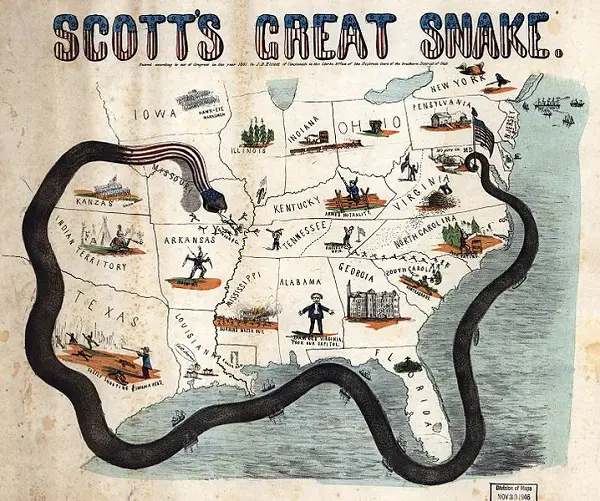

Scott’s great snake. Cartoon map illustrating Gen. Winfield Scott’s Anaconda plan, by J.B. Elliott, circa December 1861

The press dubbed the strategy the “Anaconda Plan,” naming it after the Anaconda snake that slowly squeezes its victim to death. The plan received a lot of criticism and was originally rejected because it was deemed too slow and cumbersome, according to the book Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Army:

“Public opinion held that the war would be short, and it demanded an invasion to destroy the rebellion. At the same cabinet meeting, Brigadier General Irvin McDowell, commander of the Army of Northeastern Virginia, proposed to attack and destroy the Confederate army assembling in the vicinity of Manassas Junction. Northern newspapers trumpeted ‘On to Richmond’ (the Confederate capital) and expected a victorious Union army soon to march into the city. Scott’s plan was disregarded, and McDowell’s was accepted. The result would be Union defeat at First Bull Run.”

After a series of early military defeats, the Anaconda plan was revisited though, according to the book Atlas of the Civil War:

“Only after hopes of quick victory were dashed would the public recognize the grim necessity of slowly throttling the Confederacy. Ideas that once seemed far-fetched – such as wrecking the Southern economy by preventing cotton from reaching market and causing slaves to rebel or flee their cruel overseers began to make sense as Northerners realized that their foes would not yield until deprived of the means to wage war.”

The Anaconda plan called for a full blockade of the Southern coastline and control of the Mississippi River. The Mississippi River was the South’s major inland waterway and was a valuable transportation and shipping route.

In addition, controlling the river meant the Union army could isolate Texas, Arkansas and Louisiana from the other Confederate states and split the Confederacy in two.

The Union naval blockade was established in 1861 but was ineffective, allowing around one in three blockade runners to break through.

Then, in March of 1862, the Union launched a campaign to seize control of the Mississippi River in the North and also captured New Orleans in April.

The Union’s strategy was highly so successful that it prompted the Confederates to aggressively counterattack in response, particularly in General Lee’s failed Gettysburg campaign in 1863, which caused such devastating losses that it is considered by many historians to be the beginning of the end for the Confederacy.

After the fall of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863 and Port Hudson in Louisiana on July 9, 1863, the Union won complete control of the Mississippi river.

These aspects of the Anaconda plan were important, but it was still necessary to destroy the Confederate army in order to force the South to surrender. The Union leaders at the time were reluctant to directly engage Confederate troops, much to Lincoln’s dismay.

Although Lincoln had very limited military experience, he felt very strongly that the Union should take advantage of its large army and aggressively engage the Confederates simultaneously in different locations to overwhelm them, according to a letter he wrote to his generals Buell and Halleck:

“I state my general idea of this war to be, that we have the greater numbers … that we must fail unless we can find some way of making our advantage an overmatch for his; and that this can only be done by menacing him with superior forces at different points at the same time.”

This strategy is eventually what prompted Lincoln to promote like-minded Ulysses S. Grant to the position of Lieutenant-General in March of 1864, naming him General-in-chief of the Armies of the United States in the process.

Ulysses S. Grant’s strategy to win the war was purely one of offense, according to the book Memorial Life of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant:

“So far as the strategy of the Lieutenant-General is to be described, it consisted a good deal in fighting the enemy, while localities like Richmond, Charleston, etc. were in themselves but minor considerations. He believed that hard fought battles were a mercy to the army, and that heavy lists of killed and wounded went far to reduce the totals of those sacrificed in war compared with the losses by disease through inactivity and exposure consequent upon a long-drawn-out policy of manuevering and defensive warfare. Grant believed in strategy, but it was a strategy which involved fighting the enemy, not circumventing him. The new commander saw that the only road to peace was a destruction of the rebel armies.”

The Union started to fight the Confederates more aggressively and, in 1864, General William Tecumseh Sherman led his troops on his famous March to the Sea, during which the troops captured and destroyed anything they came across. This further deprived the Confederates of the food and supplies they desperately needed.

When the capital of the Confederacy, Richmond, Va, was captured in April of 1865, the Confederate’s line of commands were completely disrupted. The invading Union forces slowly began to close in on and isolate the various units of Confederate troops across the South, forcing them to surrender.

Confederate Strategy:

At first, the Confederacy simply wanted to survive and defend its right to secede. They had no interest in invading Union territory. As the Union army went on the offense and prepared to invade the South, the Confederate army went on the defense and prepared themselves for attack.

Due to the Confederate army’s small size, Confederate President Jefferson Davis planned to avoid major battles with the Union army to prevent annihilation of his army and instead planned to only participate in small, limited engagements when the odds were in their favor.

This is referred to as a strategy of attrition – a strategy of winning by not losing and simply wearing out the enemy by prolonging the war and making it too costly to continue.

The problem with this strategy is the governors, congressmen and residents of the various border states along the Confederate perimeter requested the presence of small armies in those states to prevent against Union invasion.

This led to small armies being dispersed around the Confederate perimeter along the Arkansas-Missouri border, at several points on the Gulf and Atlantic coasts, along the Tennessee-Kentucky border, and in the Shenandoah Valley and western Virginia as well as at Manassas.

Known as the “Cordon Defense,” this spread the Confederate army so thin that Union forces could easily break through somewhere, which they did at several points in 1862.

There was also a growing demand within the Confederacy to be more aggressive and attack the Union army before they could attack them.

In response, Davis instead settled on an “offensive-defensive” strategy in which troops would be moved around to meet military needs instead of trying to defend the border and, if the opportunity presented itself, to go on the offensive and perhaps even invade the North.

To pressure Europe into helping them, the Confederates cut off Europe’s supply of cotton in an attempt to gain leverage. This backfired though when Europe instead chose to get their cotton from India and Egypt. As a result, the Confederates couldn’t earn enough money to pay for guns, ammunition or supplies.

Yet, an article by Terry L. Jones in the New York Times argues that the lack of funds caused by their withholding of cotton was only a minor issue for the Confederacy and did not ultimately cause its defeat:

“Confederate defeat has also been blamed on King Cotton diplomacy. If the Confederates had sent as much cotton as possible to Europe before the blockade became effective instead of hording it to create a shortage, they could have established lines of credit to purchase war material. This argument is true, but it misses the point. While the Confederates did suffer severe shortages by mid-war, they never lost a battle because of a lack of guns, ammunition or other supplies. They did lose battles because of a lack of men, and a broken-down railway system made it difficult to move troops and materials to critical points. Cotton diplomacy would not have increased the size of the rebel armies, and an increasingly effective Union blockade would have prevented the importation of railroad iron and other supplies no matter how much credit the Confederates accumulated overseas.”

Although the majority of the Confederate leaders opposed the idea of invading the North, Robert E. Lee was determine to do so after his surprising victory at the Peninsula and at Second Manassas in 1862.

Lee knew the South lacked the industry to sustain a long war and he believed invading the North after his recent victories would sustain a psychological blow to the Union, according to an article by Scott Hartwig on the Civil War Trust website:

“Lee understood from the beginning of the war that the Confederacy’s best hope for independence rested upon the morale of the Northern people. If they believed the war could not be won, or could only be won at too high a cost, then Southern independence became a real possibility. Confederate military successes were the means to erode morale and create this political climate. The fall elections in the North were approaching. England and France stood on the sidelines watching closely, carefully weighing whether they should recognize the Confederacy. Lee sensed a great opportunity was at hand. He believed the Union army was disorganized and demoralized. He also knew that it was receiving many reinforcements in the form of newly raised regiments in answer to President Lincoln’s July call for 300,000 volunteers. Only one move would force the Federals to place their army in the field before they had reorganized and offered the best chance to do further damage to Northern morale: Invade the border state of Maryland.”

By invading Maryland and posing a threat to cities like Harrisburg, Philadelphia and even Washington D.C., Lee believed it would encourage secessionists in those areas and would pressure Lincoln and other leaders to curtail military operations or perhaps negotiate with the Confederates.

The invasion didn’t work though and the Confederates were defeated in that campaign at the famous Battle of Antietam. That Union victory then prompted President Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which officially made the war about slavery and, in turn, prevented Britain or France from supporting the Confederacy.

Yet, this defeat didn’t stop Lee from making another attempt to invade the North in 1863. With the important city of Vicksburg, Mississippi under threat of Union attack and control of the Mississippi River at stake, Lee argued, during a meeting with other Confederate leaders in mid-May in 1863, that the best way to bring the war to an end would be to invade the North for a second time, according to the book Robert E. Lee: Legendary Commander of the Confederacy:

“Recognizing these threats, several Confederate leaders urged Lee to send some of his troops to reinforce the threatened points. Some even urged him to take command against Grant. Lee refused. The best way for the Confederacy to win, he argued, was for him to invade the North a second time. He insisted that if he could win a victory on Northern soil, Lincoln would recall his armies from the Deep South to keep the Army of Northern Virginia from marching all over the North. As he had done before Antietam, Lee also argued that a successful Southern invasion would demoralize the North and perhaps erode its will to fight.”

Lee was so popular with Davis and the other Confederate leaders that they agreed to his plan. Lee’s plan failed though when he lost the most famous battle of the Civil War, the Battle of Gettysburg in July of 1863.

The battle ended up being disastrous for the Confederates, who lost 25,000 soldiers over the course of three-day-long battle. Gettysburg is considered a major turning point in the Civil War because it caused such devastating losses for the Confederates that they were never able to fully recover.

The battle marked the beginning of the end for the Confederates. The gamble to invade the north had backfired and many historians believe it cost them the war in the end.

Lee never again attempted another invasion of the North and instead focused solely on defending whatever land they still controlled. As the war progressed though, the Confederates lost more and more ground as well as more soldiers, ammunition, food and supplies.

The war finally came to a close after General Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia became trapped by invading Union forces in Appomattox county, Va and were forced to surrender. This prompted similar surrenders by remaining Confederate troops across the South, which finally brought an end to the Civil War.

Sources:

Allen, Stephen Merrill. Memorial Life of General Ulysses S. Grant: With Biological Sketches of Lincoln, Johnson, Hayes, Garfield, Arthur, His Associates in the Government. Boston: Webster Historical Society, 1889.

Anderson, Paul Christopher. Robert E. Lee: Legendary Commander of the Confederacy. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, 2003.

Brown, Jerold E. Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Army. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2001.

Beringer, E. Richard, Herman Hattaway, Archer Jones, and William N. Still, Jr. Why The South Lost The Civil War. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1986.

Hyslop, Stephen Garrison. Atlas of the Civil War: A Comprehensive Guide to the Tactics and Terrain of The Civil War. Washington D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2009.

Stoker, Donald. The Grand Design: Strategy and the U.S. Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

“Appomatox Court House.” Civil War Trust, www.civilwar.org/learn/civil-war/battles/appomattox-court-house

Hartwig, Scott. “The Maryland Campaign of 1862.” Civil War Trust, www.civilwar.org/learn/articles/maryland-campaign-1862

Greenbaum, Mark. “Lincoln’s Do-Nothing Generals.” New York Times, 27 Nov. 2011,opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/11/27/lincolns-do-nothing-generals/

“Anaconda Plan.” Civil War Academy, www.civilwaracademy.com/anaconda-plan

“Offense or Defense?” Virginia Historical Society, www.vahistorical.org/collections-and-resources/virginia-history-explorer/american-turning-point-civil-war-virginia/wagi-3

Jones, Terry. “Could the South Have Won the War?” New York Times, 16 Mar. 2015, opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/03/16/could-the-south-have-won-the-war/

Farmer, Alan. “Why Was the Confederacy Defeated?” History Today, Sept. 2005, www.historytoday.com/alan-farmer/why-was-confederacy-defeated

Swayne, Matthew. “Union’s Strategy Trouble Prolonged Civil War.” Futurity, 26 Jun. 2012, www.futurity.org/union%E2%80%99s-strategy-trouble-prolonged-civil-war/

“Northern Plans to End the War.” U.S. History Online Textbook, www.ushistory.org/us/33h.asp

this website really helped in our school project thank you for the very helpful information

It helped a lot in my history civil war essay

This really helped me out with my U.S. History project.

This really helped me with a history project on the Civil War. Thank You!

The website was effective for helping us in History class write essays.

Thanks

😉 😉 😉

Same with me, Thanks for helping on my history poject.

Very helpful for my History Essay. Thank you!

very epic

Even many generals fail to understand the difference in tactics and strategy. Thank you for writing this concise yet thorough explanation of the strategies of the North and South during the Civil War.

Thanks this was VERY helpful for a school project thanks helped me get an A

thxs