The Civil War was one of the first wars to be documented by photography. The invention of photography in the 1820s allowed the horrors and glory of war to be seen by the public for the first time.

Dozens of photographers, some private and some employees of the army, snapped photos of the soldiers as well as the locations of Civil War battles. The images became iconic and inspired many other photographers to take their cameras onto the battlefields of future wars like WWII and Vietnam.

The majority of civil war photos are still shots of soldiers, dead and alive. This is due to the primitive nature of photography. Cameras during the days of the civil war required a 5 to 20 second exposure for each photo, thus making action shots impossible.

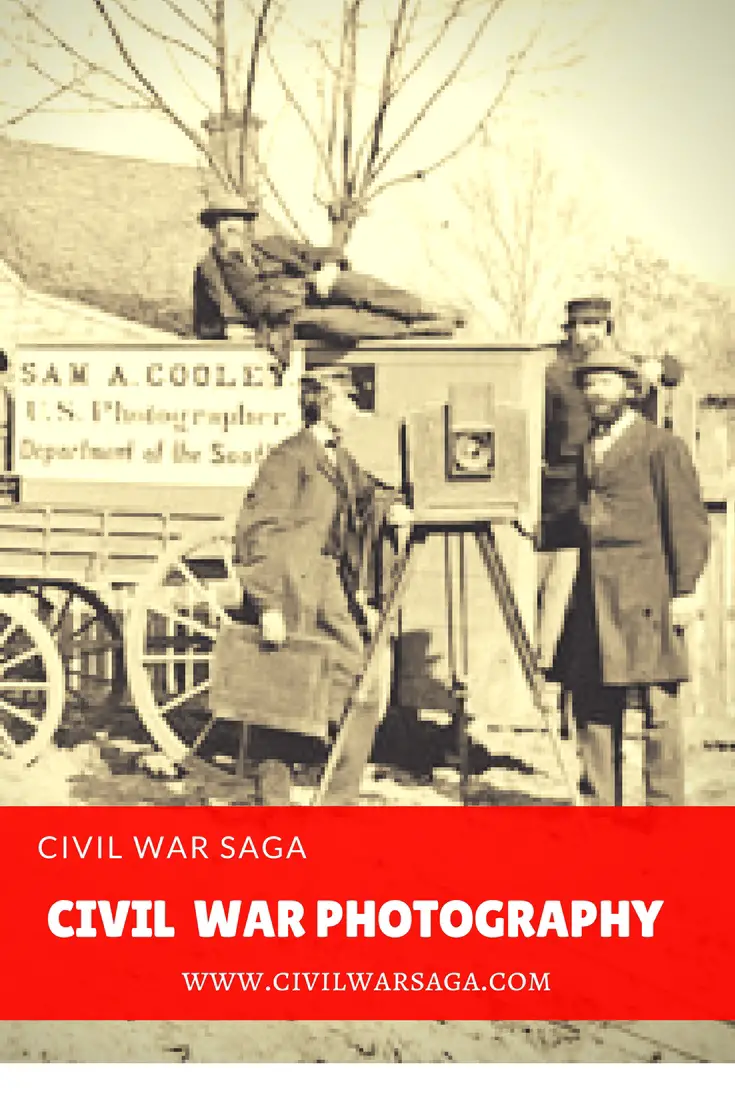

Group of photographers standing next to wagons labeled “Sam A. Cooley U.S. Photographer Department of the South”, with their camera on the left, and two African American men employed as drivers, circa 1861-1865

One of the most famous names in civil war photography is Mathew Brady. Although Brady did not take many photos himself, he hired many photographers for his studio, including James and Alexander Gardener, Timothy O’Sullivan and Egbert Guy Fox.

Photographs of the Civil War quickly became popular among the general public because of the shocking and realistic nature of the photos. These photos gave people at home the chance they never had before to see the evil of war with their own eyes. War was very often romanticized during the Victorian era and these images made it clear that the death and destruction were not something to take lightly.

Dead Confederate artillerymen, photographed by Alexander Gardner in front of Dunker Church after the Battle of Antietam, September 1862

The type of photography used during the civil war was known as wet-plate photography. The process of capturing photos was complicated and time consuming. Photographers had to carry all of their heavy equipment, including a portable dark room, to the battlefield on a wagon.

The cameras were large and hard to move around on the battlefield. Chemicals used in the process were made up of a mixture known as collodion. This mixture included dangerous chemicals like ethyl ether, acetic and sulfuric acid that had to be mixed by hand.

The act of taking a photo was a very detailed process. First the photographer positioned and focused the camera. Then he mixed the chemicals. The chemicals were then applied to a piece of plate glass to sensitize it to light. The plate was then brought into a dark room where it was immersed in silver nitrate.

The plate was placed into a light-tight container and inserted into the camera. The photographer then removed the cap on the camera for 2 to 3 seconds to expose it to light and imprint the image on the plate. The cap was replaced and the plate glass, still in its light-tight container, was taken to the darkroom where it was placed in a bath of pyrogallic acid.

A mixture of sodium thiosulfate was added to protect the image from fading and the glass was then washed, dried and varnished. This process created the negative that was then printed on paper.

Photographers also learned how to make sophisticated 3D images with these cameras, known as “stereo views.” Stereo view images were created using twin lenses placed at different angles on the same target.

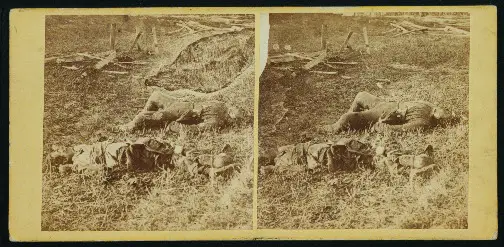

Stereo view of a group of dead Confederate soldiers after the battle of Antietam, photographed by Alexander Gardner, circa Sept 1862

The two images were then captured on a single plate glass. The different angles added more detail and depth to the image. The images were then printed on stereo viewer cards. These cards were inserted into viewer devices designed to view the 3D image.

Although there is a common saying that claims “The camera never lies,” this is not always true, even before the days of digital manipulation.

The first recorded case of photo manipulation was in 1865 when a photo of Abraham Lincoln was altered. When Lincoln was assassinated, there was a sudden demand for heroic images of Lincoln to be used as mementos.

No suitable photos existed so a photographer named Thomas Hicks took the head of Abraham Lincoln from a Mathew Brady photo and placed it on the body of John C. Calhoun from a different photo.

When Hicks placed Lincoln’s head on Calhoun’s body, he reversed his head which placed his famous mole on the wrong side of his face. This error lead to the discovery of the manipulation. Despite the obvious alteration, the photo still became the iconic image of Lincoln you see today on the five dollar bill.

Other types of photo manipulation involved the staging of photos so they would be more dramatic and shocking. It was not a secret during the civil war that many of Mathew Brady’s iconic war images were staged to create a more dramatic image.

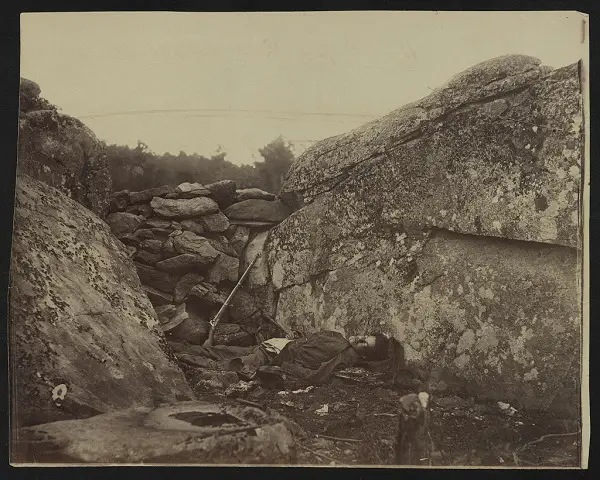

In one famous photograph titled “Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter,” taken by one of Brady’s photographers, Alexander Gardner, after the Battle of Gettysburg, Gardner had the body of a dead soldier moved to a stone wall and propped the soldier’s head on a knapsack so that it faced the camera. Gardner also placed a prop rifle on the wall next to the dead soldier.

Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, photographed by Alexander Gardner, circa 1863

In another famous photograph taken by Gardner at the Battle of Antietam, Gardner moved the bodies of dead soldiers so he could get the nearby Dunker church in the background of the photo.

In 1866, Gardner published a two-volume book, titled Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the Civil War, of nearly 100 photographs he took on the Civil War Battlefields.

Photographer George N. Barnard also published a book of photographs in 1866 titled George N. Barnard’s Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign, featuring 68 photographs of Sherman’s campaign. Some of the most iconic photos of the Civil War era come from these two photography books.

By the end of the civil war another type of photography, known as tintype, had replaced wet-plate photography. Tintype photography involved creating a direct positive on a sheet of iron blackened by paint lacquer or enameling.

Much like the wet-plate photography, after the image was burned onto the tin, the tin was then placed in a collodiun mixture. The underexposed negative was mounted against a dark metal background, which gave the image the appearance of a positive.

The photographs were quicker and faster to produce because they did not require drying and could be produced within minutes of taking the photograph. This new technology greatly advanced the art of photography and made it a faster process.

Sources:

Photography: A Cultural History, Mary Warner Marien; 2002

Duke University Libraries: Barnard and Gardner Civil War Photographs: http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/rubenstein_barnardgardner/

Famous Pictures; Altered Images: http://www.famouspictures.org/mag/index.php?title=Altered_Images

National Archives; Pictures of the Civil War: http://www.archives.gov/research/military/civil-war/photos/index.html

Civil War Trust; Photography and the Civil War: http://www.civilwar.org/photos/3d-photography-special/photography-and-the-civil-war.html

i learned a lot tysm!!!

the photos are surreal. they capture the struggles of the time.