The Confederate States of America, which existed from 1861 to 1865, was a collection of 11 states that seceded from the United States in 1860 and 1861.

The Confederacy, as it was collectively known, was one of many belligerents who fought in the Civil War.

The United States government never recognized the Confederates States of America as a legitimate government or even as a belligerent (a nation or person engaged in war) but various European countries, such as Great Britain, Spain and Brazil, granted the Confederacy belligerent status, according to an article by the Office of the Historian on the U.S. Department of State website:

“Following the U.S. announcement of its intention to establish an official blockade of Confederate ports in 1861, foreign governments began to recognize the Confederacy as a belligerent in the Civil War. Great Britain granted belligerent status on May 13, 1861, Spain on June 17, and Brazil on August 1. Other foreign governments issued statements of neutrality.”

Which States Were in the Confederacy?

The Confederate states were:

South Carolina (seceded December 20, 1860)

Mississippi (seceded January 9, 1861)

Florida (seceded January 10, 1861)

Alabama (seceded January 11, 1861)

Georgia (seceded January 18, 1861)

Louisiana (seceded January 26, 1861)

Texas (seceded February 1, 1861)

Virginia (seceded April 17, 1861)

Arkansas (seceded May 6, 1861)

North Carolina (seceded May 20, 1861)

Tennessee (seceded June 8, 1861)

When Did the Confederate States of America Form?

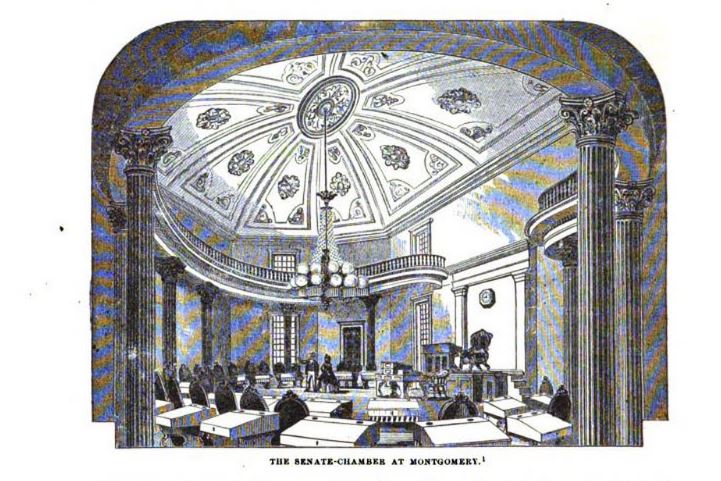

On February 4, 1861, representatives from six states, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, and Louisiana, met at the Montgomery Convention in Montgomery, Alabama to organize the Confederate States of America.

Senate Chamber at Montgomery, illustration published in the Pictorial Field Book of Civil War in United States, Vol 2, circa 1880

On February 8, 1861, the representatives announced the formation of the Confederate States of America, with its capital at Montgomery, Alabama.

Once Virginia joined the Confederacy in April of 1861, the national government was transferred to the city of Richmond in part to defend the strategically important Tredegar Ironworks there.

Who Was the President of Confederate States of America?

On February 9, 1861, Jefferson Davis was elected Provisional President of the Confederate States of America and Alexander H. Stephens was elected Provisional Vice President by the Provisional Confederate States Congress.

On November 6 , 1861, Jefferson Davis was elected President of the Confederate States of America and Alexander H. Stephens was elected Vice President in a general election, in which they ran unopposed.

On February 22, 1862, Davis and Stephens were inaugurated in Montgomery, Alabama.

Davis and Stephens worked in the White House of the Confederacy, which was located in the Confederate capital of Richmond, Va.

Did the Confederate States of America Have a Constitution?

On February 8, 1861, the Provisional Confederate Congress adopted the Provisional Confederate Constitution.

A Constitutional Convention was then held at Montgomery, AL from February 28, 1861 to March 11, 1861, during which delegates drafted a permanent constitution of the Confederacy.

The Constitution of the Confederacy was adopted on March 11, 1861 and is almost word for word the same as the constitution of the United States, except for a number of clauses that specifically address the issues that led to political disagreements between the North and the South.

For example, many of the changes in the Confederate Constitution address the issue of slavery, such as when the Confederate Constitution actually uses the word “slaves” instead of “other persons” when discussing the clause that counts slave as “three-fifths” a person and when the Confederate Constitution declares the right to own slaves, stating: “No bill of attainder, ex post facto law, or law denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed.”

The Confederate Constitution also upholds the ban that is included in the U.S. Constitution on importing slaves from any place other than slaveholding states or territories in the United States but added a clause that demands the Confederate Congress to pass laws to make this ban more effective.

The Confederate Constitution also created a new clause that made slavery legal in all Confederate states and any new territories it may acquire and states that slave owners can take their slaves into these new states or territories.

Confederate State Department Seal, illustration published in the Pictorial Field Book of the Civil War, Vol 2, circa 1880

In another clause about how individual rights in each state are universal, the Confederates added a section that states slave holders can legally take their slaves and property into any other Confederate states or territories.

Other changes the Confederates made to their constitution include:

Placing limits on the type of infrastructure spending the Confederate Congress can authorize Forbidding Congress from forgiving debts

Cutting off funding for the post office after 1863

Imposing tarrifs on certain states’ exports

Restricting congress from appropriating cash from the treasury

Issuing money bills that cite an exact dollar amount

Requiring all new proposed bills or resolutions be about one subject only

Allowing individual states to issue “bills of credit”

Taxing ships that used Confederate waterways

Allowing states to make their own river-related treaties with each other

Imposing six-year term limits on the office of President and Vice President

Providing the president with the constitutional power to fire any civil servant

Prohibiting the president from exploiting recess appointments

Prohibiting federal courts from hearing lawsuits between a state and a non-resident unless the state is the plaintiff

Prohibiting foreigners from suing states in federal court

Requiring new states to have a vote of approval by a two-thirds majority vote in the House of Representatives and a two-thirds vote in the Senate

Requiring only three states to summon a constitutional convention

Prohibiting congress from passing ammendments

Prohibiting a state from being denied equal representation in the senate

How Was the Confederate States of America Funded?

When the Confederate government was first formed it didn’t have a treasury. To generate the funds that it needed to pay for the Civil War and government expenses, it relied on loans and taxes.

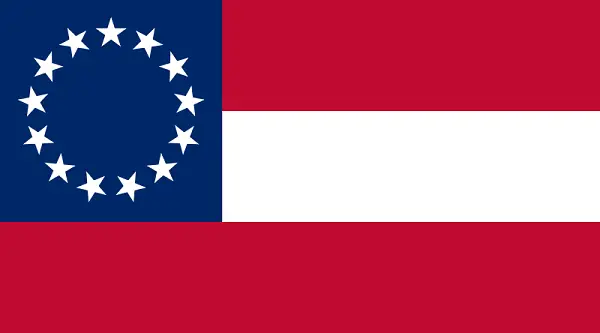

The Stars and Bars, the First National Flag of the Confederate States of America, November 28, 1861 – May 1, 1863

According to Jefferson Davis in his book A Short History of the Confederate States of America, during the Confederacy’s first 18 months, starting at the formation of the government in February of 1861 to August of 1862, the Confederacy’s total expenditure was $328,748,830.70. In round numbers, about 298,000,000 of that went to the Confederate army and $14,600,000 went to the Confederate navy.

Also during this time period, the Confederate government made $1.5 million dollars from customs, $10,539,910.70 from the war tax, $15,000,000 in bonds in February, $22,600,000 in bonds in August, $37,515,200 in call certificates, $209,930,000 in treasury and demand notes, $846,900 in one and two dollar notes and $2,645,000 in bank loans (Davis 121.)

To raise this money, the first thing the Provisional Congress did was pass a tariff law and an act authorizing a loan of $15 million dollars with the pledge of a small export duty on cotton to pay off the debt.

At the next session, plans were made to issue $20 million dollars in treasury notes, to borrow $30 million dollars in bonds and to levy internal taxes.

When the “purpose of subjugation became manifest by the action of the Federal Congress” in July of 1861, it became clear to the Confederacy that they were in for a long war and began to find ways to generate more revenue.

The Confederacy’s new plan was to issue treasury notes that could be converted into eight percent bonds with the interest payable in coin. The Confederates felt that any depreciation that might occur from the over-issue of the notes would be kept in check by the holder’s “right to fund the notes at a liberal interest payable in specie” (Davis 122.)

In order to have the money to pay the interest, the Confederate government issued an internal tax and appropriated money from imports.

The plan worked at first until various countries across Europe began issuing policies of neutrality in the war, thus refusing to assist the Confederates financially, and interest rates rose as concern grew that the Confederacy would run out of money

The Confederate government then began to try and reduce inflation by finding various ways to reduce the number of circulating notes. In February of 1864, a tax was levied on circulating notes which, within one year, greatly reduced the amount of circulating notes which, in turn, increased their value.

Yet, depreciation continued to be a problem for Confederate currency, according to Davis:

“The chief difficulty apprehended in connection to with our finances up to the close of the war resulted from the depreciation of our treasury notes, the inevitable consequence of their increasing redundancy and the diminishing confidence in their ultimate redemption.”

Military of the Confederate States of America:

The military of the Confederate States of America was comprised of three branches: the Confederate States Army, the Confederate States Navy and the Confederate States Marine Corps.

The first challenge the Confederate government faced was how to find enough weapons and ammunition for its military, according to Davis:

“At the beginning of the war there were within the limits of the Confederacy 15,000 rifles and 120,000 muskets. There were at Richmond about 60,000 old flint-muskets, and at Baton Rouge about 10,000 old Hall’s rifles and carbines. At Little Rock, Ark., there were a few thousand strands, and a few at the Texas arsenal; increasing the aggregate of serviceable arms to about 143,000. Add to these the arms owned by the several states and by military organizations, and it would make a total of 150,000 for the use of the armies of the Confederacy. There were a few boxes of sabres at each arsenal, and some short artillery swords. A few hundred holster pistols were scattered about. There were no revolvers. Before the war little powder or ammunition of any kind was stored in the southern states, and that little was a relic of the war with Mexico. It is doubtful if there were a million rounds of small-arm cartridges.”

The second problem it faced was how to feed its military, according to Davis:

“To support them it would require that the habits of our planters should be changed from the cultivation of staples for export, which had been their chief reliance in the past, to the production of supplies for home consumption. Hitherto a large proportion of our food-supplies had been imported from the West.”

The next problem the Confederates faced was how to raise, organize, train and equip the Confederate States army. The only military the Confederates had at the time of its formation were state militias which, according to Davis, the individual Confederate states were reluctant to share with the Confederate government:

“The armies and munitions within the limits of the several States were regarded as entirely belonging to them; the forces which were to constitute the provisional army could only be drawn from the several states with their consent and these were to be organized under the state authority and to be received with their officers so appointed…This is clearly seen two facts: how little was anticipated a war of the vast proportions and great duration that ensued; and how tenaciously the sovereignty and self-government of the states were adhered to.”

To recruit more officers for the Confederate Army, the Confederate government passed a law in 1861 declaring that any officers who resigned from the Federal Army would be appointed to the Confederate Army at their relative rank, which greatly contributed to the strength of the Confederacy Army’s leadership, according to the book The Oxford Companion to American Military History:

“Southerns viewed the soldier’s profession as an especially honored one, and a disproportionate number of Southern-born officers held high rank in the U.S. Army in 1860. Three hundred and thirteen officers – nearly one-third of the West Point-trained officers on active duty at the outbreak of war – resigned to join the Confederacy, contributing crucial leadership to the Southern armies.”

On April 16, 1862, the Confederate government also enacted a draft law.

Another issue the Confederate government faced was its lack of a navy, according to Davis::

“As the construction of vessels had been monopolized by the North, we found ourselves, on the opening of hostilities, without a navy, and without the machinery and accessories for building one.”

Although Great Britain issued a proclamation of neutrality in 1861, the Confederacy frequently purchased ships from individual citizens in Great Britain but the British government would often seize these vessels as they made their way back to Confederate ports even though, Davis argued, Great Britain did allow cargo ships containing munitions of war to be shipped to New York, both of which Davis saw as a violation of Britain’s neutrality claims:

“Further instances need not be adduced to show how detrimental to us and advantageous to our enemy was the manner in which England observed its hollow pretension of neutrality toward the belligerents.”

After the collapse of the Confederate government in 1865, the Confederate military force was disbanded.

End of the Confederate States of America:

The Confederate States of America came to an end after a series of devastating military defeats in the spring of 1865.

On April 3, 1865, the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia was captured by Union troops, which completely severed the Confederate government’s communication lines with its military.

On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia after being defeated at the Battle of Appomattox in Virginia and various other Confederate regiments followed suit shortly after.

On May 10, 1865, President Jefferson Davis was captured by Union forces in Georgia.

After both the Confederate capital and Davis were captured and the Confederate army surrendered, the Confederate States of America ceased to exist, according to Davis in his book The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government:

“With the capture of the capital, the dispersion of the civil authorities, the surrender of the armies in the field, and the arrest of the President, the Confederate States of America disappeared as an independent power, and the states of which it was composed, yielding to the force of overwhelming numbers, were forced to rejoin the Union from which, four years before, they had one by one withdrawn. Their history henceforth became a part of the history of the United States.”

Sources:

The Oxford Companion to American Military History. Edited by John Whiteclay Chambers II, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Davis, Jefferson. The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. Vol. II, D. Appleton and Company, 1912.

Davis, Jefferson. A Short History of the Confederate States of America. New York: Belford Company, 1890.

McCullough, J.J. “The Constitution of the Confederate States of America – What Has Changed?” J.J. McCullough, jjmccullough.com/CSA.htm

“Blockade of Confederate Ports, 1861-1865.” U.S. Department of State, United States Government, 2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/cw/106954.htm

YEET