Frederick Douglass is one of the most well-known abolitionists and orators of the Civil War era.

Born a slave, under the name Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, in February 1818 on a plantation in Maryland, Douglass was the son of a slave woman and an unknown white man.

Separated from his mother when he was only a few weeks old, Douglass never met his father and instead lived with his grandparents on the plantation. When he was 8 years old, his owner sent him to work as a house servant in Baltimore.

Despite a federal law prohibiting it, his owner’s wife taught Douglass how to read. When Douglass’ owner forbade his wife to continue teaching him, Douglass continued his reading and writing lessons by giving his food to neighborhood boys in exchange for lessons.

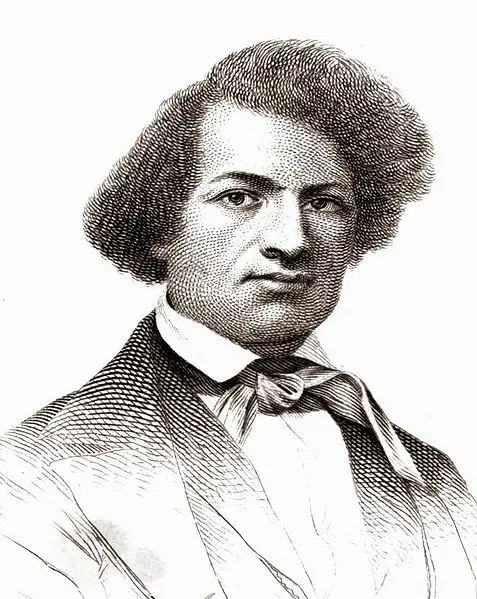

Illustration of Frederick Douglass

When Douglass was 15 years old, his owner died and he was sent to a plantation run by a notorious slave breaker known as Edward Covey. After being whipped and starved, Douglass vowed to escape slavery.

Although he was captured on his first escape attempt at the age of 18, Douglass finally escaped two years later and fled to New York City with his girlfriend, a free black woman named Anna Murray, where they married.

The newlyweds then fled to New Bedford, Mass where they changed their last name to Douglass to escape slave hunters.

Eager to continue his education, Douglass joined many organizations in New Bedford, attended a black church and attended abolitionist meetings.

Douglass also subscribed to William Loyd Garrison’s newspaper “The Liberator” and saw Garrison speak at the Bristol Anti-Slavery Society. The two quickly became friends and Garrison even mentioned Douglass in his newspaper.

Shortly after, Douglass began his long speaking career when Garrison asked him to be a lecturer for the Society for three years.

Frederick Doulgass’ first wife Anna Murray Douglass

After earning a reputation as a talented public speaker, Douglass published his autobiography titled “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written By Himself” in 1845.

Publishing the book put his freedom in jeopardy and forced him to leave the U.S. on a two year tour of England, Scotland and Ireland to avoid recapture.

Fortunately, the speaking tour finally earned Douglass enough money to return to the U.S. and purchase his freedom. The Douglass family relocated to Rochester, NY, where Douglass started his own four-page weekly newspaper called “The North Star.”

Not only an abolitionist, Douglass also believed in women’s rights. This led him to participate in the women’s rights convention at Seneca falls in 1848. Douglass also developed a close friendship with suffragist Susan B. Anthony that lasted until the day he died.

In the late 1840s and 1850s, Douglass and Garrison began to develop different views towards abolitionism that caused tension in their friendship. Garrison developed a more radical point of view, declaring that the U.S. Constitution was a pro-slavery document and the Union should be dissolved.

Douglass completely disagreed and felt dissolving the Union would isolate slaves in the South. Despite mutual friends, such as Harriet Beecher Stowe, trying to patch up the friendship, the two drifted apart.

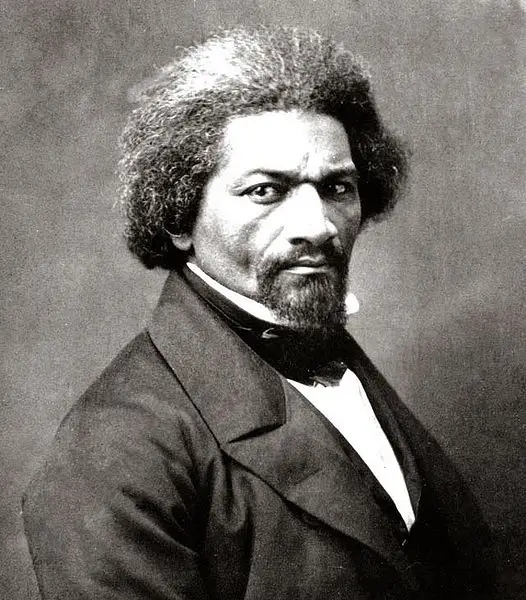

Frederick Douglass in 1866

While living in Rochester, Douglass opened his home to runaway slaves on the Underground Railroad and worked with fellow abolitionists such as Harriet Tubman and John Brown.

Douglass also helped recruit blacks for the Union army and became an adviser to Abraham Lincoln. Two of Douglass’ sons served in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, which was the first regiment of black soldiers in the Civil War.

After the war ended, Douglass held many federal offices such as assistant secretary of the Santo Domingo Commission, Marshal of the District of Columbia, Recorder of deeds and eventually U.S. minister and consul general to Haiti in the late 1880s.

Frederick Douglass and his second wife Helen Pitt

In 1882, Douglass’ wife died of a stroke after 44 years of marriage. He remarried in 1884, this time to a white woman named Helen Pitt. This inter racial marriage caused discontent among his African-American friends but Douglass was devoted to his new wife and ignored the criticism.

Douglass died of a heart attack or stroke on February 20, 1895 at the age of 77 years old. He was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York.

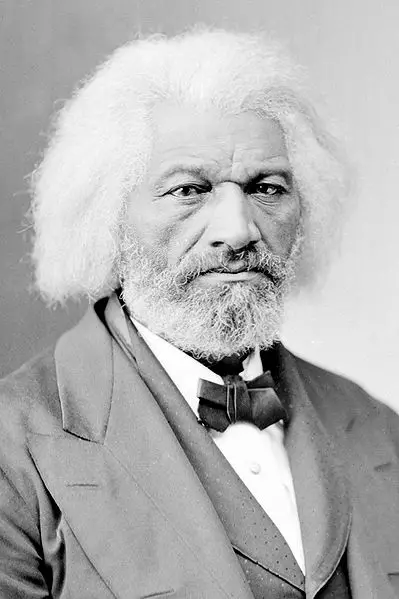

Frederick Douglass in 1880

To learn more about Frederick Douglass and the roles of African-Americans during this time period, check out this timeline of Frederick Douglass’s life or these articles about the best books about Frederick Douglass and African-Americans in the Civil War.

Sources:

The Frederick Douglass Encyclopedia. Edited by Julius Eric Thompson; James L. Conyers Jr; and Nancy J. Dawson, Greenwood Press, 2010.

“Death of Frederick Douglass.” New York Times, 21 Feb. 1895, www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0207.html

“A Short Biography of Frederick Douglass.” Frederick Douglass, www.frederickdouglass.org/douglass_bio.html

“Frederick Douglass.” PBS.org, Public Broadcast Service, www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p1539.html