Rose O’Neal Greenhow was a Confederate spy and wealthy socialite from Washington D.C.

Born into a large slave-holding family in Maryland around 1813, Rose was sent to live with her aunt in Washington D.C. after her father, John O’Neal, was murdered by one of his slaves in 1817.

In 1835, Rose married Robert Greenhow, a wealthy physician who worked as an official for the Department of State. They had eight children together and became important figures in Washington D.C. society.

After Robert was killed in an accident in 1854, Rose’s finances took a hit but she continued socializing with important political figures in Washington D.C.

When the Civil War broke out in the spring of 1861, Greenhow was recruited to become a Confederate spy by Virginia Governor John Letcher, who had set up a vast spy network in Virginia, via a U.S. Army Officer in Washington D.C. named Thomas Jordan, according to the CIA’s website:

“Letcher got his spy nest started by telling Thomas Jordan, a Virginia-born West Point graduate, to recruit Greenhow. Jordan, who had served in the Seminole Indian War and the Mexican War, was stationed in Washington. Sometime in the spring of 1861, while still a U.S. Army officer, he called on Greenhow and asked her to be an agent. (He soon left Washington and became a lieutenant colonel in the Virginia Provisional Army.) Greenhow accepted the mission enthusiastically, using her knowledge of Washington’s ways to get intelligence useful for the South. Major William E. Doster, the provost marshal who provided security for Washington, later called her ‘formidable,’ an agent with ‘masterly skill,’ who bestowed on the Confederacy ‘her knowledge of all the forces which reigned at the Capitol.'”

Greenhow was such a successful spy that she has been credited with helping the Confederates win the first battle of Bull Run in July of 1861 by sending Confederate General P.G.T.

Beauregard coded messages, via a female spy named Betty Duvall, warning him of Union General Irwin McDowell’s plans to advance on the Confederates on July 16. Greenhow hid the message in a small piece of silk and secured it in Duvall’s hair bun before sending her off, dressed as a simple farm girl, to Beauregard.

This message prompted Beauregard to request that Confederate President Jefferson Davis order General Joseph E. Johnston, stationed about fifty miles away, to bring his troops to Bull Run as reinforcement, thus allowing them to win the battle.

On July 22, Davis sent Greenhow a personal letter thanking her for her service, according to the book Encyclopedia of the American Civil War.

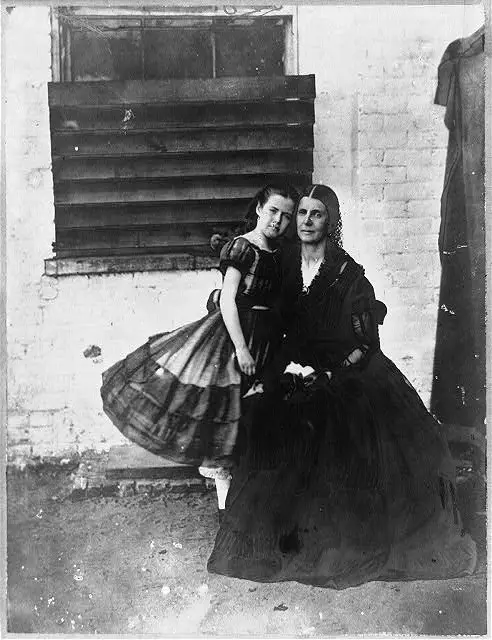

Rose O’Neal Greenhow, circa 1855-1865

The U.S. secret service suspected espionage was responsible for the Confederate victory at Bull Run and its attention quickly turned to Greenhow after Assistant-Secretary of War, Thomas A. Scott, asked Allan Pinkerton, the head of the secret service, to watch Greenhow, according to Pinkerton’s memoir The Spy in the Rebellion:

“I had not been many days in the city when one afternoon I was called upon by the Hon. Thomas A Scott, of Pennsylvania, who was then acting as the Assistant-Secretary of War, who desired my services in watching a lady whose movements had excited suspicion, and who, it was believed, was engaged in corresponding with the rebel authorities, and furnishing them with much valuable information. This lady was Rose Greenhow, a southern woman of pronounced rebel proclivities…After the departure of the Secretary I took with me two of my men, and proceeded to the vicinity of the residence of Mrs. Greenhow…Ranging the two men side by side under the broad windows in front of the house, I removed my boots and was soon standing upon their shoulders and elevated sufficiently high to enable me to accomplish the object I had in view…As the visitor entered the parlor and seated himself-awaiting the lady of the house, I immediately recognized him as an office of the regular [Union] army, whom I had met that day for the first time…In a few moments Mrs. Greenhow entered and cordially greeted her visitor…I heard enough to convince me that this trusted officer was then and there engaged in betraying his country, and furnishing to his treasonably-inclined companion such information regarding the disposition of our troops as he possessed.”

After the officer left the house, Pinkerton chased after him, in his bare feet and drenched by rain, and followed him to the War Department where Pinkerton’s bizarre appearance and behavior prompted the guards to arrest him.

He was later released and the officer he was following was arrested and imprisoned for a year at Fort McHenry.

Greenhow also wrote about the incident in her memoir, “My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington,” but claimed her friend was innocent and suggested Pinkerton was the one in the wrong:

“I must here record a circumstance which will go far to prove that a certain gentleman in black does not always take care of his own. The Chief Detective, Allen [Pinkerton’s alias was Major E.J. Allen], having gone out on some errand of mischief, on returning about nine o’clock encountered a gentleman who was at that time Provost-Marshal of the city, and who was about to call to make a visit at my house. Allen, being ignorant of or disregarding his official position, attempted to arrest him. He ran, pursued by Allen, until he reached the Provost’s quarters, when, ordering out his guard, he arrested Allen, and held him in close confinement until the next morning, regardless of his oaths, or his prayers, to be allowed to send a message to Lincoln, or Seward, or McClellan. By these indirect Providence seems to have watched over and averted destruction from me.”

The secret service continued watching Greenhow over the next few weeks and finally arrested her, on August 23, on charges of espionage.

“Halt or I Fire” illustration of Pinkerton’s arrest published in “The Spy of the Rebellion” by Allen Pinkerton circa 1883

Greenhow later described her arrest in her memoir:

“From several persons on the side-walk at the time, en passant, I derived some valuable information; amongst other things, it was told me that a guard had been stationed around my house throughout the night, and that I had been followed during my promenade…This caused me to observe more closely the two men who had followed… A few moments after, and before I could open the door, the two men above described rapidly ascended also, and asked, with some confusion in manner, ‘Is this Mrs. Greenhow?’ I answered, ‘Yes.’ They still hesitated; whereupon I said, ‘Who are you, and what do you want?’ ‘I come to arrest you.’…I rapidly glanced my eye to see that my signal had been understood, and remarked quietly, ‘I have no power to resist you; but had I been inside of my house, I would have killed one of you before I submitted to this illegal process.’”

Greenhow was immediately placed under house arrest and her home was searched. After asking to withdraw to her bedroom to change her clothes, Greenhow managed to destroy some coded messages she was carrying before a female officer arrived to strip search her.

Hearing of her arrest, Greenhow’s various friends and family members came to the house and were immediately arrested as well.

In her memoir, Greenhow stated that the officers got drunk on the rum and brandy in her liquor cabinet and threatened to rape or sexually assault the female prisoners but Pinkerton’s memoir makes no mention of this.

Greenhow’s friends and family were eventually allowed to leave that afternoon and managed to smuggle Greenhow’s messages and incriminating papers out of the house in their boots and stockings.

As Greenhow’s house arrest wore on, Pinkerton brought several other female spies to her home, earning it the nickname “Fort Greenhow.”

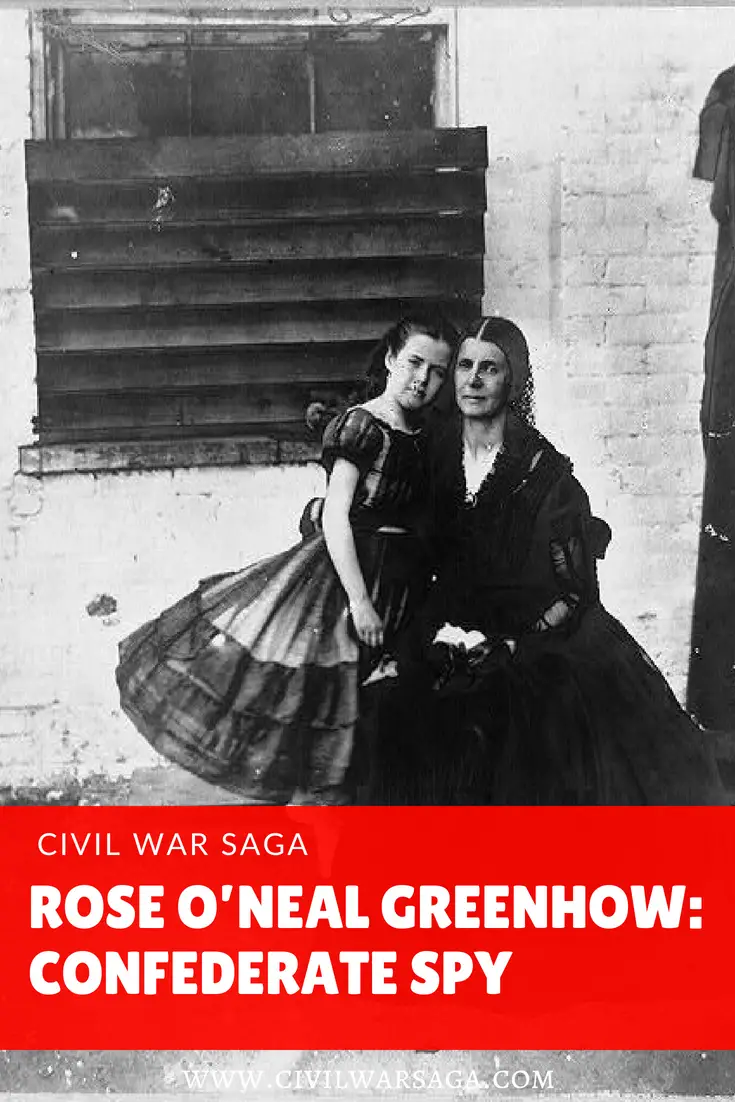

Yet, Greenhow was still allowed visitors and continued to smuggle messages to the Confederate army. Out of frustration, Pinkerton incarcerated Greenhow and her eight-year-old daughter, Rose, in the Old Capitol Prison in January of 1862.

Confederate spy Rose O’Neal Greenhow and her daughter, Rose, imprisoned at the Old Capital Prison in 1862

While in prison, Greenhow rebelled by hanging a Confederate flag from a window of the prison and sending secret messages to the Confederates.

She described the poor living conditions at the Old Capital Prison in her prison diary:

“I can conceive no more horrible destiny than that which was now my lot. At nine o’clock the lights were put out, the roll was called every night and morning, and a man peered in to see that a prisoner had not escaped through the keyhole. The walls of my room swarmed with vermin and I was obliged to employ a portion of the precious hours of candlelight in burning them on the wall, in order that myself and child should not be devoured by them in the course of the night. The bed was so hard that I was obliged to fold up my clothing and place them under my child; in spite of this she would often cry out in the night, ‘Oh, mama, the bed hurts me so much.’…In addition to all other sufferings was the terrible dread of infectious diseases, several cases of small pox occurring, and my child had already taken the camp-measles, which had broken out amongst them. My clothes, when brought out from the wash, were often filled with vermin; constantly articles were stolen.”

Later that year, in March, the Greenhows were examined by a War Department Commission and in May they were deported to Richmond, Virginia where Greenhow was awarded $2,500 by Jefferson Davis as “an acknowledgment of the valuable patriotic service rendered by you to our cause.”

The following summer, in August of 1863, Greenhow sailed to Europe, with her daughter, as an unofficial representative to gain support for the Confederate cause.

While little Rose attended the Sacred Hearts Convent school in Paris, Greenhow met with many British and French officials, including Queen Victoria and Napoleon III (cousin to Prince Napoleon and nephew to the infamous Napoleon I).

While in London, Greenhow published her prison diary, My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule At Washington, which was well-received and sold many copies.

After a year in Europe, Greenhow boarded a British blockade-runner, the Condor, bound for America. When the ship ran aground off the coast of North Carolina on October 1st of 1864, Greenhow escaped in a small rowboat, to avoid the Union gunboat pursing the ship.

The small rowboat capsized before she reached the shore and Greenhow was dragged under by her purse filled with heavy gold coins she had received as royalties for her book.

Greenhow was buried with full military honors at the Oakdale Cemetery in Wilmington, North Carolina. Her headstone reads: “Mrs. Rose O’N. Greenhow, a bearer of dispatchs [sic] to the Confederate Government.”

Her daughter, Little Rose, continued attending school in Paris after her mother’s death and eventually returned to America in 1871.

Rose O’Neal Greenhow, circa 1855-1865

Sources:

“A Spy of the Rebellion: Being a True History of the Spy System of the United States Army”; Allen Pinkerton; 1883

“Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History”; edited by David Stephen Heidler; 2000

“My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington”; Rose O’Neal Greenhow: 1863

“America’s Women: 400 Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates and Heroines”; Gail Collins; 2009

“Women’s Suffrage in America”; Elizabeth Frost-Knappman; Kathryn Cullen-DuPont; 1992

Central Intelligence Agency; Intelligence in the Civil War: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/additional-publications/civil-war/p5.htm

The New York Times; The Wild Rose of Washington; Cate Lineberry; August 2011: http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/08/22/the-wild-rose-of-washington/

History.com: Rose Greenhow is Arrested: http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/rose-greenhow-is-arrested

Britannica: Rose O’Neal Greenhow: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/245259/Rose-ONeal-Greenhow

Smithsonian Institute: Rose O’Neal Greenhow: http://www.civilwar.si.edu/leaders_greenhow.html

Duke University Library: Rose O’Neal Greenhow Papers: http://library.duke.edu/rubenstein/scriptorium/greenhow/

National Archives: Seized Correspondence of Rose O’neal Greenhow: http://www.archives.gov/research/arc/topics/civil-war/greenhow.html

This is amazing thank you so much!

this is helpful for my school project

i love this❤❤❤❤