Sarah Emma Edmonds was a female soldier and spy in the Civil War.

The following are some facts about Sarah Emma Edmonds:

Sarah Emma Edmonds’ Childhood:

Edmonds was born on a farm in New Brunswick, Canada in 1841, to Isaac Edmonds, of Scotland, and Elizabeth Leeper, of Ireland.

In her memoir, Unsexed, or the Female Soldier, Sarah Edmonds stated that her family was overprotective, making her feel “sheltered but enslaved” and she described her father as the “stern master of ceremonies.”

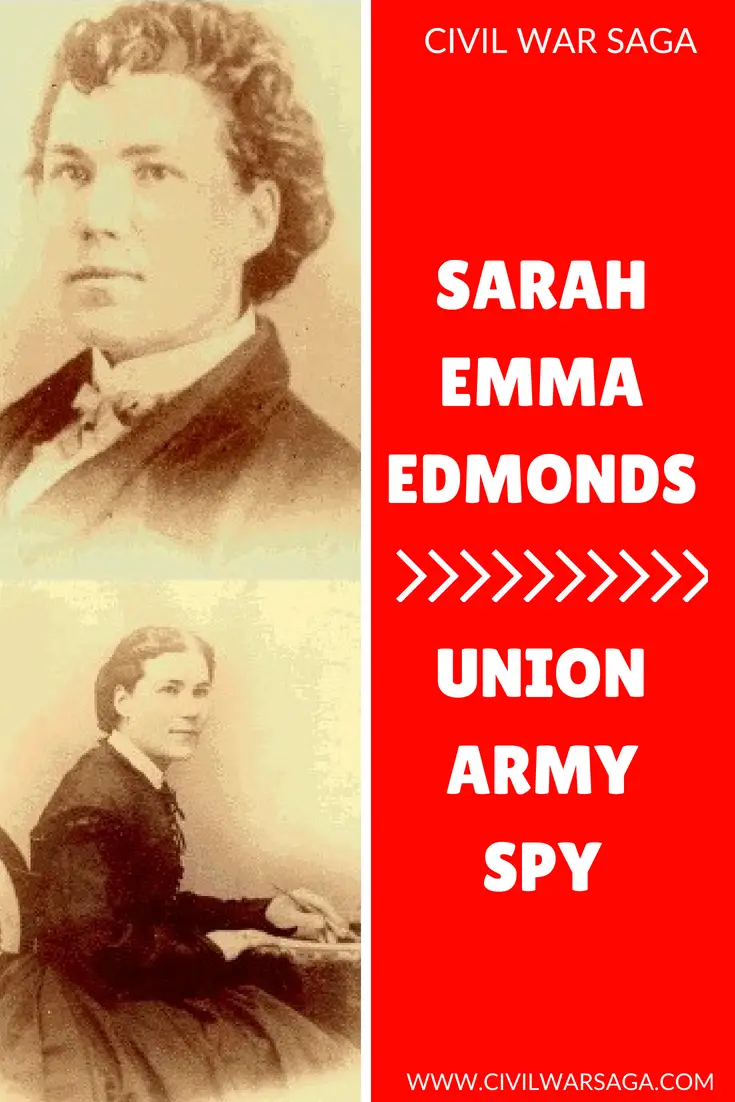

Sarah Emma Edmonds

When her father tried to marry her off to a neighbor at age 16, she ran away from home, changed her name to Emma Edmonds and got a job as a salesgirl in a millinery shop, according to the book More Than Petticoats: Remarkable Michigan Women:

“The milliner’s shop was a place of peace until her father discovered her whereabouts. In 1858 Emma Edmonds fled again. This time she changed more than her name. Years later, details of Emma’s disappearance came to light. She’d seen an advertisement for jobs selling bibles and religious books, so Emma cut her hair, spent her savings on men’s clothing, and applied for the job. She was hired and began her life as Frank Thompson.”

Sarah Emma Edmonds in the Civil War:

In her memoir, Edmonds stated that while working as a bible salesman in Flint, Michigan, she was sitting in a train station when she heard the news about the outbreak of the Civil War and knew she had to take action:

“I was aroused by my reverie by a voice in the street crying ‘New York Herald – Fall of Fort Sumter – President’s Proclamation – Call for seventy-five thousand men!’ This announcement startled me, while my imagination portrayed the coming struggle in all its fearful magnitude…It is true, I was not an American – I was not obliged to stay here during this terrible strife – I could return to my native land where my parents would welcome me to the home of my childhood, and my brothers and sisters would rejoice at my coming. But these were not the thoughts which occupied my mind. It was not my intention, or desire, to seek my own personal ease and comfort while so much sorrow and distress filled the land. But the great question to be decided, was, what can I do? What part am I to act in this great drama? I was not able to decided for myself – so I carried this question to the Throne of Grace and found a satisfactory answer there.”

Just a month later, on May 25, 1861, Edmonds signed up as a male field nurse in the Second Volunteers of the United States Army under her alias Franklin Flint Thompson.

Edmonds continued her hospital work for many months until March of 1862, when she was reassigned as a mail carrier for her regiment.

Only a few months later, after one of General McClellan’s spies was caught and executed by the Confederate army, Edmonds volunteered for the open position, as she described in her memoirs:

“But was I capable of filling it with honor to myself and advantage of the Federal Government? This was an important question for me to consider ere I proceeded further. I did consider it thoroughly, and made up my mind to accept it with all of its fearful responsibilities.”

Edmonds wrote in her memoir that her first spy mission involved darkening her skin with silver nitrate to pose as a slave named “Cuff” in a nearby Confederate military camp.

Wood Engraving of Sarah Emma Edmonds by R. O’Brien, published in “The Female Spy of the Union Army” in 1864

While there, she helped build ramparts and worked in the kitchen where she eavesdropped on conversations.

Edmonds escaped a few days later when she was assigned as a Confederate picket and returned to tell McClellan himself of the information she gathered on the Confederate’s local troop size, available weapons and location of numerous “Quaker Guns” (logs painted to look like cannons from a distance) that the Confederates planned to use in Yorktown.

A few months later Edmonds said she infiltrated the Confederate army again, this time as a female Irish peddler named Bridget O’Shea.

Edmonds returned from the trip with valuable military information as well as a beautiful horse and a wound on her arm where the horse had bit her while she was retrieving medical supplies from the saddlebags.

After her regiment was transferred to Virginia in 1862, Edmonds continued her work as a spy, going undercover again as “Cuff” and later as an African-American laundry woman in a Confederate camp, a position that allowed her to steal valuable papers from officer’s jackets which she brought back to her regiment.

Edmonds stated that she was present at many historic battles, such as the Battle of Antietam in September of 1862, during which she nursed a mortally wounded soldier who confessed to Edmonds that he was a actually a woman in disguise, according to Edmonds memoir:

“I listened with breathless attention to catch every sound which fell from those dying lips, the substance of which was as follows: ‘I can trust you and will tell you a secret. I am not what I seem, but am female. I enlisted from the purest motives, and have remained undiscovered and unsuspected…I wish you to bury me with your own hands, that none may know after my death that I am other than my appearance indicates.’… I remained with her until she died, which was about an hour. Then making a grave for her under the shadow of a mulberry tree near the battle-field, apart from all the others, with the assistance of two of the boys who were detailed to bury the dead, I carried her remains to that lonely spot and gave her a soldier’s burial, without coffin or shroud, only a blanket for a winding sheet. There she sleeps in that beautiful forest where the soft southern breezes sigh mournfully through the foliage, and the little birds sing sweetly above her grave.”

In the spring of 1863, Edmond’s stated that her regiment was transferred to the army of Ulysses S. Grant in preparation for the Battle of Vicksburg.

Steel Engraving of Sarah Emma Edmonds by Geo E Perine, published in 1865 edition of “Nurse and Female Spy in the Union Army”

It was around this time that Edmonds developed malaria and found herself in a conundrum. Unable to admit herself to a military hospital out of fear of being discovered, Edmonds decided to leave her unit and seek medical attention in a private hospital.

After recovering and leaving the hospital in Cairo, Illinois, Edmonds saw an army bulletin in the local post office listing Private Frank Thompson as a deserter.

Unable to return to her previous duties, Edmonds spent the rest of the war working as a female nurse at hospitals in war torn regions like Virginia and West Virginia.

While working in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, Edmonds met a widower from New Brunswick named Linus H. Seeyle and began a courtship.

Some historians doubt Edmonds stories and suspect she may have embellished the truth in order to sell more copies of her memoir, according to the book The Mysterious Private Thompson:

“The most dramatic parts of her book were her stories of espionage: the first trip behind enemy lines at Yorktown, her exploits while dressed as an irish peddler woman, her successful reconnaissance while disguised as a female slave during the Second Battle of Bull Run, and her dramatic escape from the Confederate cavalry in Kentucky. These stories were – and are – impossible to verify, but, true or not, they added a great deal of drama to the book, and are the source of the enduring popular belief that Emma was a spy. There are also events that could not have happened to her because she was documented to be somewhere else at the time. For example, Emma’s regiment was not at Antietam, yet she wrote about being there, and even included a melodramatic story of the dying woman soldier, so similar to Clara Barton’s experience, which Emma may have heard or read at the time. Emma also wrote about the siege at Vicksburg, which occurred several months after she left the army, as though she had been present. It is possible, however, that the source for that material was [her friend] Jerome Robbins, who had been there and may have written to Emma about it.”

Sarah Emma Edmonds After the Civil War:

In 1864, Edmonds published her memoir, Unsexed, or The Female Soldier, which was later published under the titles The Female Spy of the Union Army, and The Nurse and Spy in the Union Army. The book quickly became a best seller.

On April 27 in 1867, Edmonds and Seeyle married at the Wendell House Hotel in Cleveland, OH and briefly moved back to Canada before returning to the United States where they traveled across the U.S. in search of work, stopping in Michigan, Ohio, Texas, Illinois, Louisiana and Kansas.

The couple lost three children to illness but had two adopted two boys from an orphanage Emma ran in Louisiana in the late 1870s.

Still upset about being branded a deserter and irritated that she wasn’t eligible for a pension due to her gender, Edmonds petitioned the War Department for a full review of her case.

Various stories of women who had served in combat were starting to come out but none of them had yet been awarded a pension.

Edmonds at first tried to hide her true identity by applying for the necessary proof of her service using only her initials, S.E.E. Seeyle, on her paperwork but when the War Department continued to request her full name she decided to be upfront about her situation, according to the book The Mysterious Private Thompson:

“To that Adjutant Genl. State of Michigan my full name is Sarah Emma Evelyn Seeyle. I enlisted and served as Franklin Thompson in Co “F” 2nd Mich Vols. And refer you to Capt Damon Stewart of Flint Mich, Lieut Wm Turner of same, Capt Wm R Morse, Lawrence Kansas of Flint Mich, Gen O.M. Poe of Sherman’s staff. I would say if you don’t want to give me the certificate of service just say so. Sarah Emma E. Seeyle.”

Edmonds’ comrades came out in full support of her quest to get a pension and spoke very highly of her during interviews and in their official affidavits. Captain Morse later gave an interview to the Kansas City Star in which he stated:

“Franklin was known by every man in the regiment, and her desertion was the topic of every campfire. The beardless boy was a universal favorite, and much anxiety was expressed over her safety. We never heard of her again during the war, and could never account for her desertion.”

Yet some of her other comrades, such as William Boston, stated that there were rumors all along that Edmonds was a girl and many in the regiment believed she deserted after an alleged lover, an inspector in the army, resigned.

Among the many affidavits in her case file, Edmonds herself also submitted a sworn statement in which she tried to avoid, for reasons unknown, confirming or denying her claims of espionage she had written about in her memoirs:

“I make no statement of any secret services. In my mind there is almost as much odiom attached the word ‘spy’ as there is to the word ‘deserter.’ There is so much mean deception necessarily practiced by a spy that I much prefer everyone should believe that I never was beyond the enemy’s lines rather than to fasten upon me by oath of a thing I despise so much. It may do in wartime, but it is not pleasant to think upon in time of peace.”

In March of 1884, two bills were submitted to the House of Representatives: one was to remove the charge of desertion from Edmonds record and the other was to award her a pension of $12 a month. The report that accompanied the pension bill stated:

“Truth is ofttimes stranger than fiction, and now comes the sequel, Sarah E. Edmonds, now Sarah E. Seelye, alias Franklin Thompson, is now asking this Congress to grant her relief by way of a pension on account of fading health, which she avers had its incurrence and is the sequence of the days and nights she spent in the swamps of the Chickahominy in the days she spent soldiering. That Franklin Thompson and Mrs. Sarah E.E. Seelye are one and the same person is established by abundance of proof and beyond a doubt. She submits a statement . . . and also the testimony of ten credible witnesses, men of intelligence, holding places of high honor and trust, who positively swear she is the identical Franklin Thompson. . . .”

On July 5 of 1884, a Special Act of Congress finally granted Edmonds a veteran’s pension of $12 a month but the bill to clear her name moved slowly and wasn’t passed until July of 1886.

She then had to apply for the back pay and bounty she would have earned if she hadn’t been charged with desertion, a process which took another two years.

Since her case generated a lot of publicity, Edmonds became something of a celebrity in her small town of Fort Scott and was awarded membership into the Civil War veterans organization, the Grand Army of the Republic, in 1897.

In the fall of 1897, Edmonds fell ill with another bout of malaria and although she started to recover a few months later, by the end of the summer she was suffering from paralysis possibly brought on by a stroke.

Edmonds passed away on September 5, 1898 and was buried in a local cemetery in La Porte, Texas. In 1901, Edmonds was re-buried with military honors at Washington Cemetery in Houston.

Sources:

Civil War Home: Sarah Emma Edmonds: www.civilwarhome.com/edmondsbio.htm

The Civil War Trust: www.civilwar.org/education/history/biographies/sarah-emma-edmonds.html

The Mysterious Private Thompson: The Double Life of Sarah Emma Edmonds; Laura Leedy Gansler;

More Than Petticoats: Remarkable Michigan Women; Julia Pferdehirt; 2007

The Female Spy of the Union Army: The Thrilling Adventures, Experiences and Escapes of a Woman, As Nurse, Spy, and Scout, in Hospitals, Camps and Battlefields; Sarah Emma Evelyn Edmonds; 1864

who were Sarah’s sisters/brothers did she have any? thanks

She didn’t have any sisters or brothers

Wrong, she was the youngest in her family, with four sisters and one brother.

too long to read but i did it anyways this is some great info

thx. im doing a project on her

wbcdwq,j

WOW! i did not know anything about emma until i clicked on this site