Civil War prison camps were notoriously filthy and disease-ridden camps, warehouses, forts and prisons that held an estimated 400,000 captured Civil War soldiers, as well as spies and political prisoners, during the war.

Some of these prisoners included members of John Wilkes Booth’s family, who were held at the Old Capital Prison in Washington D.C. following Abraham Lincoln‘s assassination, as well as women prisoners-of-war, who were held at prisons such as Castle Thunder in Richmond.

It is estimated around 56,000 of these prisoners died in the prison camps. The high mortality rate was due to the lack of food, clothing, sanitation and shelter for the high volume of prisoners.

Prisons at the time were not designed to hold hundreds of thousands of prisoners and supply shortages caused by the war added to the problem.

Libby Prison in 1865

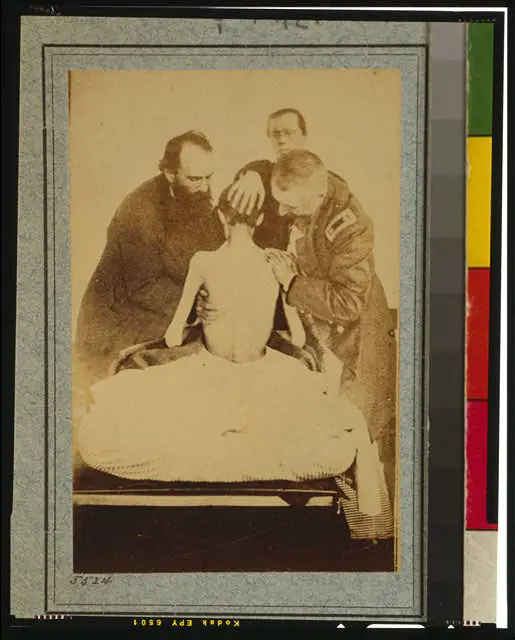

As a result, the prisoners suffered from malnutrition and starvation as well as diseases like typhoid, dysentery, smallpox, malaria and cholera.

These prisons also lacked adequate sewer or sanitation facilities for the large number of prisoners, causing the local waterways, rivers and low-lying areas to overflow with the prisoner’s waste.

Not only did prisoners suffer physically, they suffered mentally as well. According to an article in National Geographic, a large number of prisoners became depressed and sometimes catatonic, while others, looking for a quick death, taunted guards to shoot them.

A Federal prisoner being examined by doctors after his release from prison

The U.S. established more than 150 of these prison camps during the Civil War, all of which were filled to capacity. Some of the more well-known camps include:

Andersonville in Andersonville, Georgia

Arsenal Penitentiary in Washington D.C.

Belle Isle in Richmond, Va

Cahaba Prison in Cahaba, Alabama

Camp Butler in Springfield, Illinois

Camp Chase in Columbus, Ohio

Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

Camp Douglas in Chicago, Illinois

Camp Ford in Tyler, Texas

Camp Morton in Indianapolis, Indiana

Camp Randall in Madison, Wisconsin

Camp Sorghum in Columbia, South Carolina

Castle Thunder in Richmond, Virginia

Castle Williams on Governor’s Island in New York

Camp Dennison in Cincinnati, Ohio

Fort Jefferson in Key West, Florida

Elmira Prison in Elmira, New York

Florence Stockade in Florence, South Carolina

Fort Columbus on Governor’s Island in New York

Fort Delaware in Delaware City, Delaware

Fort McHenry in Baltimore, Maryland

Fort Pulaski in Chatham, Georgia

Fort Slocum in New Rochelle, New York

Fort Warren in Boston, Massachusetts

Franklin and Armfield Office in Alexandria, Virginia

Gratiot Street Prison in St. Louis, Missouri.

Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia

Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C.

Pierce County Jail in Blackshear, Georgia

Castle Pinckney in Charleston, South Carolina

Point Lookout in Scotland, MD

Rock Island Arsenal in Rock Island, IL

Some prison camps were more notorious than others. Andersonville prison, with its mortality rate of 29 percent, is one of the most infamous prisons of the Civil War.

Andersonville Prison

Elmira prison in New York had a 25 percent mortality rate and Fort Delaware lost so many prisoners it was dubbed the Fort Delaware Death Pen.

When prisoners couldn’t take life in the camp anymore, they made their escape. One of the easiest ways prisoners escaped was by pretending to be sick or dead, hoping the guards would carry them outside where they would then get up and walk away. Others disguised themselves as slave labor and walked out with visiting slaves.

Prisoners also made elaborate escape plans by tunneling under the prison walls, such as in Libby prison where 109 Union soldiers dug their way out in a 60 foot tunnel using only clam shells and case knives. Most prison escapes failed though, and those caught were severely punished with hard labor or torture.

The public reaction to conditions in these prison camps were one of horror, but both the Confederate and Union army refused to do anything about it.

Many women volunteered as nurses and aides in the prisons in order to better help the prisoners. When they couldn’t get nursing jobs, some of these women, such as Union spy Elizabeth Van Lew, brought the prisoners much needed food and medical supplies, using the opportunity to gather valuable military information to pass along to military officials.

Despite the horrific conditions and the public’s opposition to the camps, the prison camps only came to an end when the Civil War ended in 1865.

After the Confederates surrendered, prisoners on both sides were released but many of them found themselves miles from home with no way to get there.

Many prisoners ended up living in the wild trying to survive off whatever they could hunt or gather. Others made their way to Washington D.C. where they finally found transportation, food and shelter with the help of high-ranking military officials like General Ulysses S. Grant.

Many of these Civil War prison camps still exist and are maintained by the U.S. National Park Service, who has opened them up to the public for tours and visits.

Sources:

“Civil War Prisons”;William Best Hesseltine; 1962

“The Civil War Naval Encyclopedia”; Spencer C. Tucker; 2010

National Geographic; U.S. Civil War Prison Camps Claimed Thousands; Yancey Hall; July 2003

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/07/0701_030701_civilwarprisons.html