John Wilkes Booth was born May 10, 1838 near Bel Air, Maryland, into a distinguished family of actors. He was the 9th child of actor Junius Brutus Booth and his wife Mary Ann.

Although a talented actor from a young age, John was emotional unstable and egotistical. He had trouble sharing the spotlight with his brothers who were also gifted actors.

As a teenager, Booth attended a boarding school near Cockeysville, Maryland. While away at the school, Booth had an encounter with a gypsy who read his palm and told him that he was going to be rich and famous one day but he was also going to die young under a bad circumstance. She further warned him to become a priest or missionary to escape his fate.

Booth did not heed the gypsy’s advice and continued to pursue acting while also dabbling in politics in the 1850s when he joined the Know-Nothing party. This political party dedicated themselves to limiting the number of immigrants entering the United States each year.

Booth’s first acting debut took place at the Baltimore theater in 1856. He continued acting in Philadelphia until 1859, when he joined a Shakespearean stock company in Virginia.

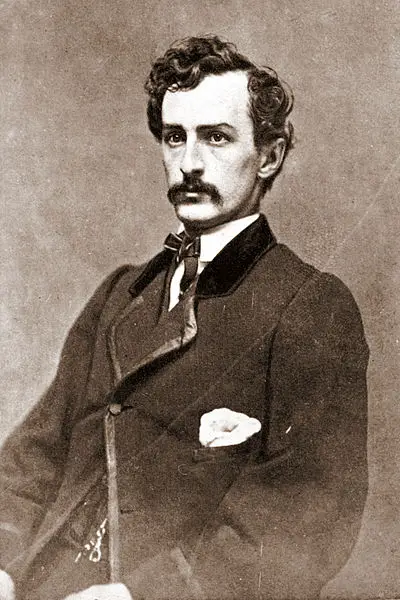

John Wilkes Booth in 1865

While rehearsing in Richmond, Booth spontaneously volunteered for a Virginia Militia group, the Richmond Grays, as they marched towards Charleston to assist in the hanging of John Brown.

Brown had been tried and convicted of treason after his failed raid of a federal armory at Harper’s Ferry, where he hoped to start a slave uprising in the south.

Also present at the hanging was Stonewall Jackson, who was then a professor at the Virginia Military Institute and had been ordered to provide security at the execution.

After the hanging, Booth went on a tour of the deep south with the Shakespeare company and was well received by critics and audiences. He was known for being a very passionate, physical and almost acrobatic performer. Booth toured the country throughout the Civil War. He also served as a spy for the Confederate army and helped smuggle medicine and supplies to the army.

Booth’s professional success continued and by the early 1860s he was earning around $20,000 a year (the equivalent of about $500,000 today). He ventured into some business deals that included buying a $8,000 plot of land in Boston in the newly created Back Bay neighborhood. He also invested in some oil companies but lost a great deal of money in a bad investment in 1864.

As a southerner, Booth was a strong supporter of slavery and held a deep and outspoken hatred for Abraham Lincoln, even though his own parents were abolitionists and his brother Edwin Booth voted for Lincoln in 1864. Coincidentally, the feelings of animosity were not mutual between Booth and Lincoln as Lincoln was a fan of Booth and even invited him to the White House one evening after watching him perform at Ford’s Theater in 1863, to which Booth declined.

Booth was arrested and charged with treason in St. Louis in 1863 for publicly stating he “wished the President and the whole damned government would go to hell.” He was released after paying a fine and pledging his allegiance to the Union.

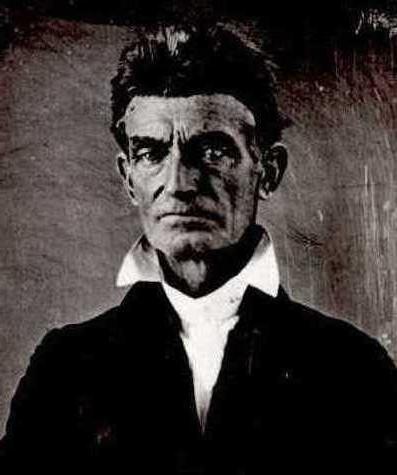

John Brown

During the summer of 1864, Booth began a plan to abduct Abraham Lincoln and hold him for ransom. He recruited friends and Southern sympathizers to hatch the plan, which would involve taking Lincoln to Richmond and exchanging him for Confederate prisoners.

A strange coincidence occurred around this same time, either in the fall of 1864 or the early winter of 1865, when John Wilkes’ brother Edwin Booth saved Robert Todd Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln’s son, from being hit by an oncoming train in New Jersey. It is not known if John Wilkes Booth knew of his brother’s heroic actions or not.

Also around this time, John Wilkes Booth met Lucy Lambert Hale, the daughter of U.S. Senator John P. Hale, in February of 1865 and fell madly in love with her. The courtship allegedly caused a romantic rivalry between Booth and Robert Todd Lincoln, who was also courting the young woman. It is believed that Booth and Hale became secretly engaged shortly after. Hale was not aware of Booth’s hatred towards Lincoln or his plans.

In March, Booth and his conspirators heard that Lincoln would be attending a showing of “Still Waters Run Deep” at the Ford’s Theater on March 17. Booth laid out a plan to intercept Lincoln’s carriage on the way to the theater but his plans fell through when Lincoln decided to skip the theater and speak to a regiment of Indiana soldiers.

The south surrendered the very next month, after a series of military defeats, and Booth and his friend Louis Powell attended Lincoln’s speech outside of the White House on April 11.

During the speech, Lincoln suggested extending the right to vote to educated black citizens and black veterans. This statement enraged Booth, who turned to his friend and declared, “That means nigger citizenship. That is the last speech he will ever make.”

Three days later, Booth discovered that Lincoln would be attending that evening’s performance of “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theater in Washington D.C.

He gathered his conspirators and assigned them each a task. At 6 p.m., Booth went to the theater and tampered with the door of the presidential box so he could jam it shut once he got inside that evening.

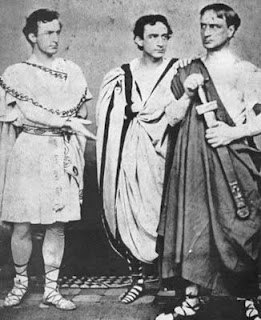

John Wilkes Booth (left) performing with his brothers

Around 10 p.m., Booth returned to the theater and went straight to the presidential box. Entering the box, he pointed his derringer pistol at the back of Lincoln’s head and fired.

Booth then pulled out a dagger and slashed one of Lincoln’s companion, Major Henry Rathbone, before jumping from the balcony. Booth somehow lost his footing as he jumped, although it is not clear if he had been grabbed by Rathbone or if he had caught his spur on the flag draped on the balcony railing. He fell to the stage and landed hard on his left leg, breaking the bone.

After landing on the stage, Booth shouted “Sic semper tyrannis!” (The Virginia state motto meaning: Thus always to tyrants) and then shouted “The south is avenged!” before making his escape to the alley where his horse was waiting.

A major manhunt ensued and Booth was found 11 days later on April 26, hiding in a tobacco barn on a farm in Virginia. One of Booth’s conspirator, David Harold, was in the barn with him. An article published in the New York Times, on April 28 of 1865, detail the events of his capture:

“When Harold saw the preparations for firing the barn, he declared his willingness to surrender, and said he would not fight if they would let him out. Booth, on the contrary, was immediately defiant, offering at first to fight the whole squad at one hundred yards, and subsequently at fifty yards. He was hobbling on crutches, apparently very lame. He swore he would die like a man, etc. Harold having been secured, as soon as the burning hay lighted the interior of the barn sufficiently to render the scowling face of Booth, the assassin, visible, Sergeant Boston Corbet fired upon him and he fell. The ball passed through his neck. He was pulled out of the barn, and one of his crutches, and carbine and revolvers secured; the wretch lived about two hours, whispering blasphemes against the government, and messages to his mother, desiring her to be informed that he died for his country. At the time Booth was shot he was leaning upon one crutch and preparing to shoot his captors. Only one shot was fired in the entire affair – that which killed the assassin.”

After being accused of disobey orders to capture Booth alive, Boston Corbett later explained that he shot Booth out of necessity after he saw him raise his gun and believed he was about to fire at the officers.

Officers found a red leather diary on Booth’s body that contained two entries and photos of five women, one of whom was his secret fiance Lucy Hale.

Some of Booth’s conspirators, Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, George Atzerodt, were tried in June of that year and hanged at the Old Arsenal Penitentiary on July 7.

Booth’s family was also arrested on suspicion of being Booth’s conspirators and some were even imprisoned with the other conspirators but were later released when officials found no evidence linking them to the crime.

The remaining conspirators Samuel Mudd, Samuel Arnold, Michael O’Laughlen and Edmund Spangler were given prison sentences but were eventually pardoned in 1869. John Surratt was captured and tried in 1867 but was released after the jury could not reach a verdict, resulting in a mistrial.

Another possible conspirator, Sarah Slater, was mentioned during the trials but was never found.

Sources:

Right of Wrong, God Judge Me: The Writings of John Wilkes Booth; John Wilkes Booth

New York Times; Booth Killed; April 28 1865: www.iment.com/maida/familytree/burnett/nyt-28apr1865.htm

National Museum of American History: Abraham Lincoln: An Extraordinary Life: americanhistory.si.edu/exhibitions/small_exhibition.cfm?key=1267&exkey=696&pagekey=726

Library of Congress: Assassination of President Abraham Lincoln: memory.loc.gov/ammem/alhtml/alrintr.html

Encyclopedia Britannica: John Wilkes Booth: www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/73713/John-Wilkes-Booth

In rethinking history I wonder if Abolitionist were behind the assignation of Lincoln. Abolitionist for the most part did not want the Blacks sent back to Africa.

Lincoln was thinking seriously about sending the former Slaves back to Africa so was the claim that John Wilkes Booth really a Southern Sympathizer or was that a claim made by Abolitionist to deflect the assignation away from them. And there were Abolitionist that were part of the Lincoln Administration.

Who exactly said Booth was a Southern Sympathizer?